Michael Joseph G. Ostique

University of the Philippines Open

Abstract

Given its high growth in recent years and resilient demand amidst the covid-19 pandemic, trade in services has become a lucrative component of the national income of ASEAN Member States (AMS) and the ROK, so the effect it receives from a positive shock like digitalization is worth studying. Using OLS regression, the digitalization of trade in services reveals a disparate impact across ASEAN-Korea, with Singapore far above the digitalization-services trade curve, while Indonesia, Viet Nam and the ROK exhibit lower than projected per capita trade in services as a result of digitalization; also, even when lesser developed AMS exhibit fast growth and average impact from digitalization, their total trade volumes remain low. Nevertheless, throughout ASEAN-Korea, digitalization has a positive impact on all sectors of trade in services, even when recent literature covering OECD identify certain sectors like construction as negatively affected. This positive impact of digitalization is significant in all sectors, except manufacturing exports, and highest in financial services, telecommunications, transport, construction, insurance and pension, and IP. Using this and the trade patterns of both ASEAN and the ROK, it can be concluded that certain sectors like financial services, transport and insurance warrant attention from ASEAN-Korea, especially post covid-19. The digitalization impact on these sectors may be maximized by creating complementarities through linkages, increased competitiveness, and evidence-based policy on productivity clusters and local digitalization strategy as well as structural transformation of services using insights from the country performances and sector-level indicators, respectively, derived from this research.

Keywords: ASEAN-Korea, Digitalization, International Trade in Services, covid-19

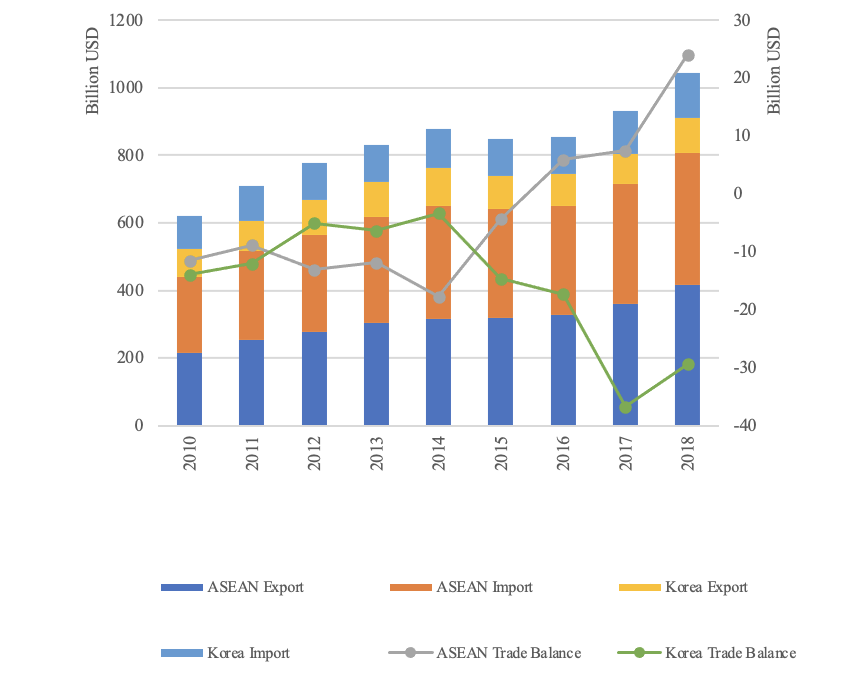

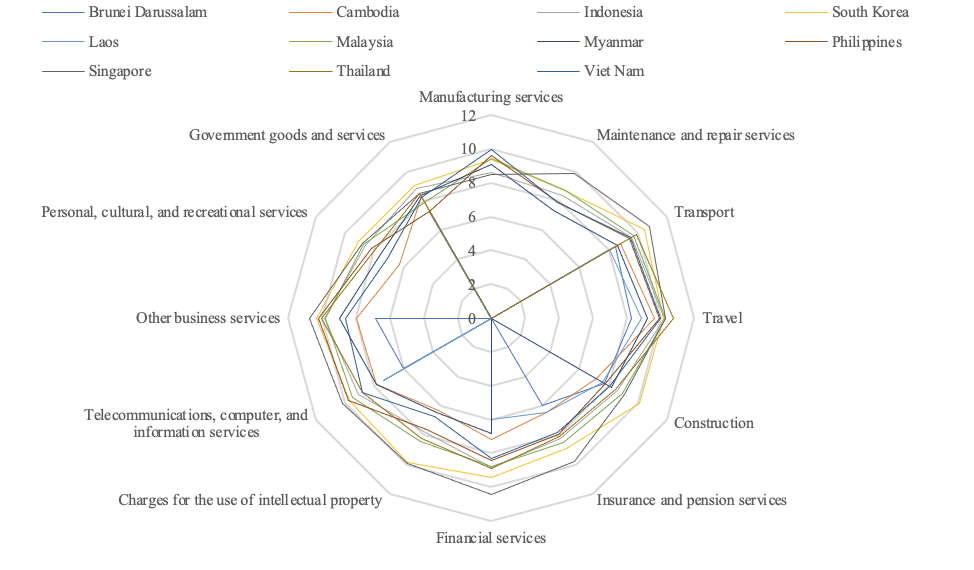

Trade in services is the new engine of growth in ASEAN, accounting for 60% of its foreign direct investment inflow and 50.1% of its total gross domestic product (GDP); of this, Singapore takes the largest portion, with 101% of its GDP coming from trade in services, but all other ASEAN Member States (AMS) have high services trade components as well from 6.1% in Indonesia to 34.5% in Cambodia, with only Indonesia, Myanmar, and Laos falling shy behind the global average of 13.3% (ASEAN Integration Report, 2019: 30). This figure is only 14.5% in the ROK (World Bank, 2019), despite being a more developed and mature economy. Further, as shown in Figure 1, while the services trade balance of ASEAN has been increasing, that of the ROK’s has been decreasing, necessitating further exports trade to alleviate the deficit. However, data from the World Trade Organization show that bilateral services trade between ASEAN and the ROK remains modest, with only Singapore, Malaysia, and to a lesser extent, Viet Nam having recognizable levels and, even then, only in certain sectors like maintenance and repair, transport, insurance, financial services, and telecommunications. This reflects the scant 5.7% overall trade share and 5.9% annual trade growth of the ROK’s services in ASEAN (ASEAN Integration Report, 2019: 135). By using these country and sector-level data, the effect on trade in services by a shock like digitalization may be determined and maximized.

Figure 1. Total exports, imports, and balance of the services trade of AMS and the ROK from 2010 to 2018.

Data source: data.wto.org

Digitalization metrics augment trade in services

Lopez & Ferencz (2018) show that a mere 10% increase in digital connectivity leads to a 3.2% increase in exports of telecommunications sector, but the effect is negative in construction, wholesale and retail services trade. Likewise, according to Choi (2010), doubling of internet usage leads to a 2-4% increase in services trade and an increase in internet access further facilitates this. These supplement the empirical model of van der Marel (2011) that identifies liberalization, deregulation, good governance, institutions, harmonization of jurisdictions, and factor endowments such as high-skilled labor and, more notably, information and communications technology (ICT) in the EU as the determinants of trade in services.

ASEAN-Korea focus and full digital index will reveal accurate projections for this region

However, studies have so far employed proxies; for example, internet use for digital connectivity, and ICT for comparative advantage in services specialization, and these proxies are mere components of overall digitalization. In addition, these studies are limited to specific blocs such as EU so the effects of digitalization metrics may differ when compared with ASEAN-Korea, especially across the various sectors of services trade. These issues are addressed in this paper through the examination of unique sectoral and country performances of ASEAN-Korea, and the use of the digital adoption index (DAI), which is representative of the supply-side digitalization of businesses, people, and governments; DAI is superior in its exhaustive metrics, number of countries covered, segregation of measurements across user groups, and employment of scaled index to represent digital technologies adoption relative to other countries’ (World Development Report, 2016).

Digitalization of trade in services should be top priority moving forward

Although digitalization also impacts other components of an economy such as consumption and investment, trade is most actionable for ASEAN-Korea institutions, which themselves are determinants of trade in services. Within trade, services will benefit most from digitalization given it is the ROK’s largest sector but already suffering from low labor productivity and declining growth, and is not as favored by government policies as the industrial economy (World Trade Organization, 2015). In ASEAN, it is a main source of employment and income expansion, and is the sector poised for domestic strengthening through technological access, as enshrined in Article 18 of the ASEAN-Korea Trade in Services Agreement. The developed and more mature economies of Singapore and Malaysia plus the large base and fast growth rate of services in the industrializing and lesser developed economies of ASEAN respectively complement the ROK’s services outlook. More importantly, the covid-19 pandemic has showcased the resilience but under-utilization of services: while trade in goods has slumped, services such as distance education, online banking, e-tourism, software development, and recreation, among others gained popularity, exhibiting potential for subsequent wider adoption.

ASEAN-Korea trade in services exhibits progress from digitalization but disparate

Digitalization has a significant effect on the overall trade in services of ASEAN-Korea, even at a stringent 1% level and the adjusted R-squared reveals that digitalization accounts for the variation in services trade for up to 45% in exports and 61% in imports, as shown in Table 1. This supports earlier studies but, whereas those were limited to few indicators, Table 1 shows that overall digital adoption per se has a larger cumulative effect. Further, a single unit increase in digital adoption results in an exorbitant increase of 1,209% in exports and 1,491% in imports.

Table 1. Effect of digitalization (measured via Digital Adoption Index) on exports and imports of services of all AMS and the ROK. -coefficient regression results against log of exports and imports.

| logExports | logImports | |

| Digital adoption index | 2.5722*** | 2.7669*** |

| std. error | 0.60842 | 0.4732 |

| Observations | 22 | 22 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.4455 | 0.6125 |

Constants estimated but not reported; DAI values range 0-1; ***significant at 1%

Source: own calculations using data from data.wto.org

|

|

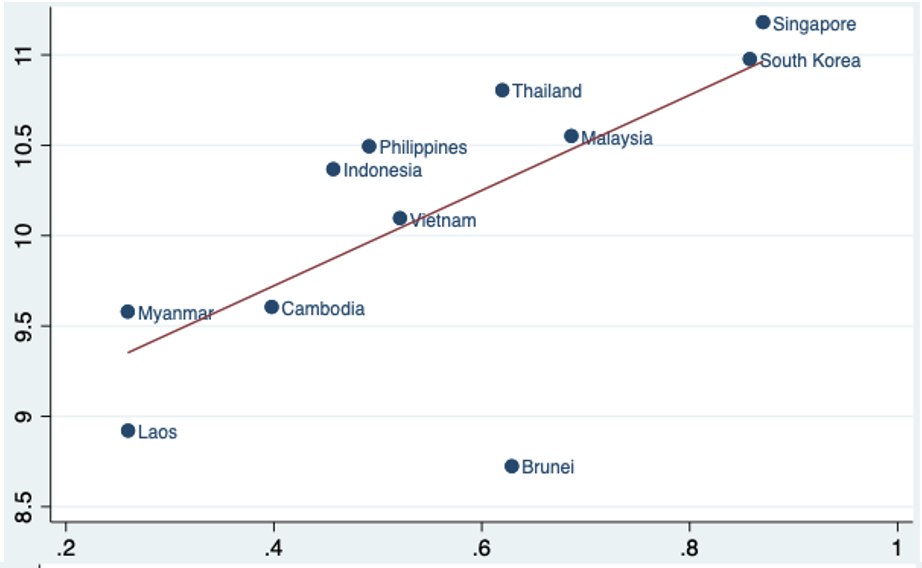

Figure 2. Effect of digitalization (independent) on log of exports (left) and log of per capita exports (right) of AMS and the ROK in 2016. Source: own calculations using data from data.wto.org

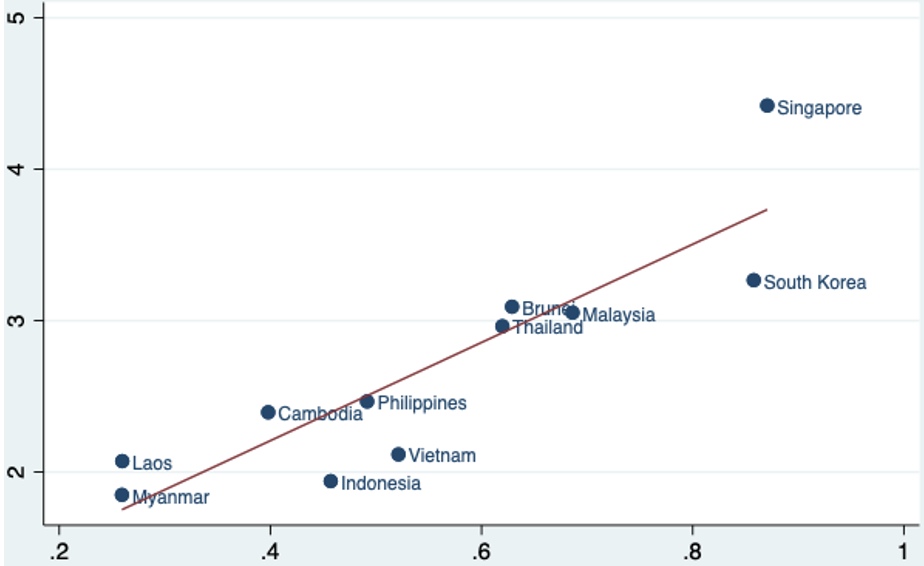

At country-level, as in Figure 2, digitalization affects AMS and the ROK disproportionately; Laos and Brunei have the lowest export level likely due to low growth rate and volume respectively and Cambodia, despite having the second fastest growth rate in ASEAN, lags in export volume. Nevertheless, adjusted per capita, these AMS perform above projection, while the more populous Indonesia, Viet Nam, the ROK, and to a lesser extent, the Philippines, lag behind. To address these gaps, ASEAN-Korea may step in to address the digitalization lag in underperforming markets; even better, to pull up the regional curve to a level near Singapore or those seen in more developed blocs like EU and OECD. In fact, within OECD, the ROK is already one of the poorest performers in productivity, digital skills, data accessibility and digital uptake (OECD, 2017) so optimizing digitalization to the level of the ROK’s, more so Singapore’s or OECD’s, will reap larger scale production and trade. But, as shown in Figure 3, ASEAN-Korea bilateral trade in services is meagre and concentrated among a few.

Figure 3. Total exports of AMS and the ROK with other AMS (intra-ASEAN), the ROK, and the world.

Data source: data.wto.org

ASEAN-Korea trade is harnessed through complementarity

Based on classical international trade theory, trade occurs when countries specialize and export goods they have comparative advantage in, and the creation of trade then increases the welfare of both exporting and importing countries. Hindley & Smith (1984) prove that these concepts could be applied to trade in services to determine patterns of trade. However, unlike goods trade, comparative advantage and complementarity of services are less understood as they are yet in early stages, making qualitative-quantitative depictions like Figure 4 pivotal in analysis.

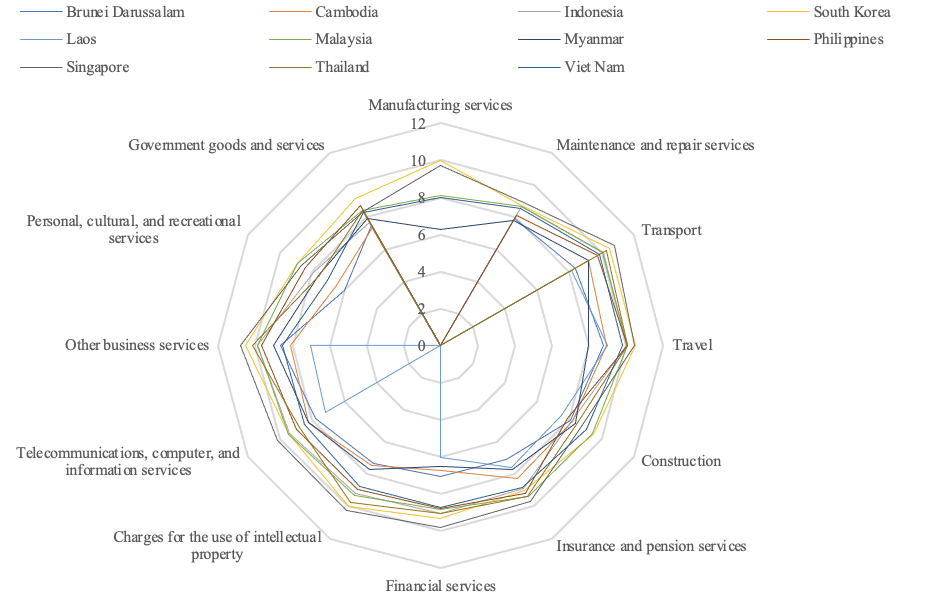

Figure 4. Sectoral breakdown of log of all exports (top) and log of all imports (bottom) of services of AMS and the ROK in 2018.

Source: own calculations using data from data.wto.org

However, where one would expect specialization, Figure 4 shows that, in general, trade in services crowds towards certain sectors and avoids others, with the possible exception of the ROK and Singapore in financial services, IP, construction, and insurance and pension services exports and in manufacturing services imports. These are expected given the highly industrialized ROK and Singapore require larger services support in manufacturing, and provide spillover services from their already large construction and IP industrial sectors. At the same time, the financial hubs of Singapore and the ROK have been leading the production and trade of financial services in the region. But for the rest of the sectors, capital endowment or comparative advantage do not matter as much as they do in trade of goods, in which countries that have productivity and efficiency advantages for a certain good exports more of that good and import what they cannot produce efficiently. This trend in services deviating from goods trade pattern follows earlier observations in OECD countries wherein trade in services interactively uses inputs of production from both exporting and importing countries of transport services (Lennon et al., 2009).

This has few implications for the ASEAN-Korea partnership in digitalization. Firstly, as countries lose endowment advantages, cost becomes the primary determinant of trade; hence, digitalization must be implemented with this consideration. Secondly, as both importers and exporters participate in both the production and trade in services, a limiting factor, such as cost, inefficiency, substandard infrastructure or restrictive regulation, in one country is sufficient to curb bilateral trade. Lastly, because capital endowment ceases to be country-specific, each country is required to both import and export services transactions (Lennon et al., 2009). Hence, ASEAN-Korea must focus its digitalization efforts toward lowering costs, liberalizing services trade, and keeping all members of the bloc at the same pace.

Digitalization has successfully developed the services production and trade in ASEAN-Korea

As shown in Table 2, digitalization has positively and significantly increased trade in services. Whereas EU and OECD suffer from the negative impact of digitalization in reduced demand in several sectors, ASEAN-Korea experiences positive impact from digitalization across the board and this might be due to trade in services being yet in its infancy, digitalization not yet rendering diminishing returns and, most possibly, AMS and the ROK having been successful in adopting digitalization. This should allay simmering fears regarding the threats digital economies pose on increasing unemployment or increasing prices of goods and services, at least in the foreseeable future. However, although the effect is both positive and significant, its magnitude varies widely. The largest impact is seen in financial services – a unit increase in digitalization increases export of roughly 9,176%, but in manufacturing services, no significant impact is observed. Liu et al. (2020) might explain this: the development of the services sector competes for resources with manufacturing activities and enhances the revealed comparative advantage of sectors that use these activities intensively but not of other manufacturing sectors. Already, this is seen in “premature aging” economies such as the Philippines, in which industrialization is compromised in favor of services. Likewise, the fast growth of services in lesser developed AMS and deindustrialization of the ROK must be addressed. According to Lim (2012), ROK’s deindustrialization in the context of a rising services economy may be alleviated by focusing on sectors whose productivity rise more rapidly and which contribute growth to other sectors to a larger degree such as telecommunications and financial services. This empirical finding is in line with the findings in Table 2, showing the sectors that should be the priority of ASEAN-Korea: aside from financial services and telecommunications, the digitalization of transport, construction, insurance and pension, and IP drive growth. In theory, digitalization of all sectors would be ideal but the limited resources demands an allocation based on returns (but also other welfare effects beyond the scope of this paper).

Table 2. Effect of digitalization (measured via Digital Adoption Index) on the sectors of international trade in services among AMS and the ROK in 2014 and 2016. -coefficient regression results against log of sectors.

| EXPORTS | ||||||||||||

| logmfg | logmain | logtrans | logtrav | logcons | logins | logfin | logip | logtel | logoth | logper | loggov | |

| Digital adoption index | 0.8638 | 1.9875* | 3.37*** | 1.623** | 3.72*** | 3.79*** | 4.53*** | 4.72*** | 2.36*** | 2.677** | 2.80*** | 1.948* |

| std. error | 0.7229 | 1.1229 | 0.4520 | 0.6813 | 0.6104 | 0.7198 | 0.7663 | 0.7891 | 0.5231 | 0.9609 | 0.7401 | 0.6463 |

| Observations | 21 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 17 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 21 |

| Adjusted

R-squared |

0.0374 | 0.1322 | 0.7221 | 0.1825 | 0.6555 | 0.6253 | 0.6269 | 0.6723 | 0.5334 | 0.2731 | 0.4391 | 0.2878 |

| IMPORTS | ||||||||||||

| logmfg | logmain | logtrans | logtrav | logcons | logins | logfin | logip | logtel | logoth | logper | loggov | |

| Digital adoption index | 2.96** | 1.163** | 2.90*** | 3.01*** | 2.30*** | 2.65*** | 3.35*** | 3.11*** | 3.07*** | 4.07*** | 2.94*** | 2.40*** |

| std. error | 1.2479 | 0.421 | 0.6592 | 0.5944 | 0.5907 | 0.6428 | 0.78 | 0.7983 | 0.542 | 0.6892 | 0.7515 | 0.5184 |

| Observations | 21 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 20 |

| Adjusted

R-squared |

0.3663 | 0.3216 | 0.4662 | 0.5399 | 0.4148 | 0.4435 | 0.5060 | 0.4413 | 0.6081 | 0.6403 | 0.4427 | 0.5174 |

Independent variable: digital adoption index; dependent variables: logged values of the international trade in services in: mfg: manufacturing services on physical inputs owned by others, main: maintenance and repair, trans: transport, trav: travel, cons: construction, ins: insurance and pension, fin: financial, ip: intellectual property, tel: telecommunications, computer, and IT, oth: other business services, per: personal, cultural, and recreational, gov: government

Constants estimated but not reported

*significant at 10%, **significant at 5%, ***significant at 1%

Source: own calculations using data from data.wto.org

Linkages must be strengthened or established to promote complementarity of services

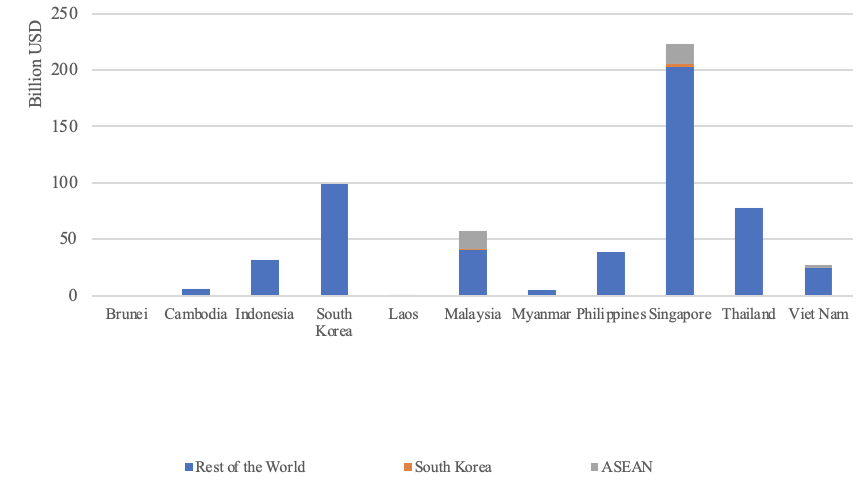

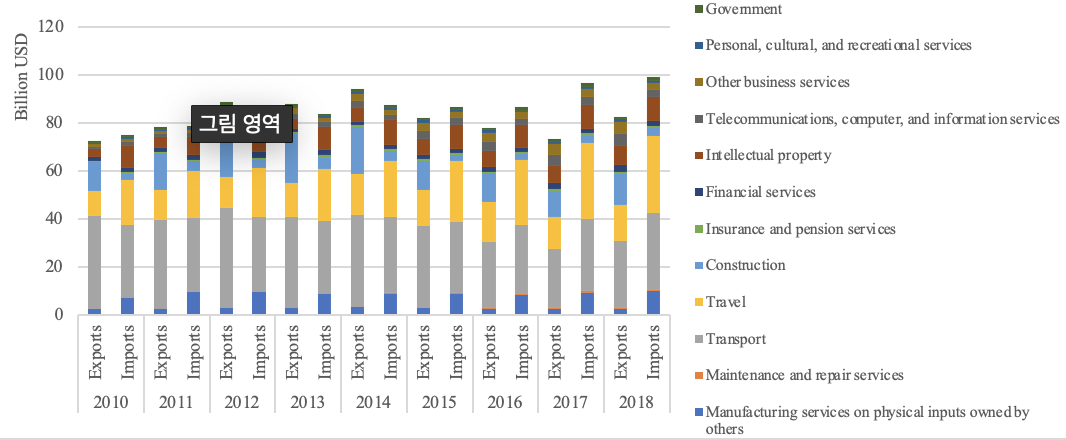

There is, however, a mismatch in the sectors that derive the largest benefit from digitalization versus those that are traded more frequently. In the ROK, for example, Figure 5 shows that most of services trade are in manufacturing, travel, transport, construction, and IP services. Although the last three return large values of trade upon digitalization, as in Table 2, they occur in large deficit. In ASEAN, the pattern is not any better as trade is dominated by transport (25%) and travel (28%), while lucrative sectors such as construction (1.1%), IP (5.9%) and telecommunications (6%) remain underserved (ASEAN Integration Report, 2019: 33). Worse, in both the ROK and ASEAN, insurance and pension, and financial services constitute a tiny share; in ASEAN, 2.4% and 5.1% respectively (ASEAN Integration Report, 2019: 33). These are lower than the UNCTAD-calculated averages for developing Asia, let alone developed, which should be at least 6.9% for financial services, 10.1% for telecommunications and 20.5% business services including insurance and pension – the biggest drivers, supposedly, in developing economies after travel and transport (Klasen, 2020).

Figure 5. Total value of exports and imports of services in the ROK in 2018.

Data source: data.wto.org

But the intra-ASEAN trade pattern is different. Travel (44.5%) grabs an even larger share as other critical sectors shrink. This travel success story is brought about by ASEAN’s initiatives in liberalizing travel exports, which in turn returned faster growth, more jobs, and larger foreign exchange earnings, and in liberalizing travel imports that brought in competition, best practices, skill and technologies, and capital – both resulted in a huge 12% growth rate between 2003 to 2016, with 43% of tourists coming from within ASEAN itself (Asian Development Bank, 2018). More importantly, according to The ASEAN Post (2020), digital technologies in the form of online booking, data management of online transactions, automation of customer services, all-in-one online travel agents with real-time availability and price information, added to an already digitally competitive industry, are what drive the rapid growth and rise in income; in fact, online travel is already ASEAN’s most established digital economy.

However, the fact that other sectors have yet to take off reveals that ASEAN services are still largely non-tradable. Domestic value-add shares are high across all AMS, indicating production and consumption start and end within a country, while foreign value-add shares have been consistently low; a slight increase was found only in Brunei, Cambodia, Viet Nam and Philippines, showing an increasing affinity towards imported intermediates in these markets (ASEAN Integration Report, 2019: 62). In the ROK, Yoon & Kim (2006) observe that the over-protection of services reduces supply and raises costs which, in turn, induces demand towards more expensive domestic providers. The ROK had attempted to address this malaise by opening up domestic service industries such as e-business, design, education, and medical services. These, along with other sensitive sectors such as health, social, and cultural services, may be unilaterally liberalized. But while this might spur domestic consumption, it further fragments the services sector; on the other hand, regional cooperation forges linkages that confer comparative advantage (Yoon & Kim, 2006). Na et al. (2015) suggest how comparative advantage through complementarity of services may be achieved in IT services of East Asia: the ROK must focus on technology, Japan on content, and China on market and hardware. For ASEAN-Korea, this is determined by the relative advantages of members, similar to Figure 2, but at subsector level. Overall, members must cooperate in building a regional data set for productivity analysis, leverage the varying levels of services by creating clear linkages, and improve industrial competitiveness.

Case study: Regional integration of the ASEAN insurance sector

Insurance, a lucrative sector identified in Table 2, is ramped up for integration in ASEAN with the ASEAN Insurance Framework, which aims for full liberalization by 2021 in few subsectors, especially life. One of the objectives is to invigorate the still low insurance penetration despite an increasing growth rate. The huge trade deficit offers opportunities for intra-ASEAN players to capture a chunk of this expanding market. But incongruencies in liberalization commitments among AMS threatens integration efforts if it exacerbates the development gap among AMS as the lesser developed are also among the least liberalized. Moreover, ASEAN is composed of heterogenous populations with differing predisposition and exposure to risks, as well as income level and demographic indicators. Finally, the differing regulatory regimes also heighten underwriting risks for firms, given ASEAN enforcement mechanisms are yet limited.

Digitalization addresses these challenges by de-fragmenting the ASEAN insurance market and linking insurance services to form a complementary regional value chain around the comparative advantage of each AMS. Among the prospective benefits of digitalization include leveraging data for actuarial decision-making, delegating and integrating vertical services across AMS as digital technologies enable synergistic operations, acquiring distant customers through remote marketing, and providing customers with digital platforms for transactions. Had these been implemented prior to the covid-19 pandemic, the current burden on individuals and governments of AMS to finance hospitalizations and mortality would not be as severe.

Economic shocks are reversed by digital adoption

Thus, liberalization and integration alone are not adequate; digitalization offers benefits neither one fulfils. Further, an ASEAN-Korea partnership amplifies the benefits of digitalization through access to a larger market, complementarities in a wider range of services subsectors, institutional support, and formulation and implementation of regional policies that will otherwise remain unheeded.

However, the covid-19 pandemic is threatening to upend the gains of ASEAN-Korea in digitalization and trade in services. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis demonstrated how a similar fall in demand for services inevitably leads to reduced national income and employment levels (UNCTAD, 2009). But what’s unique about this pandemic is the immediate supply shock, followed by a demand shock, especially in sectors where the mode of service delivery requires physical proximity of the buyer and seller, such as travel, transport or business services that still follow brick-and-mortar models. In these cases, digitalization acts by reversing the supply shock via enhanced productivities, employment effects, interactions with institutions and public governance (Elding & Morris, 2018). For example, digitalizing the transport sector entails smart automations for routing of cargo such that a larger volume may be processed at one time; also, human physical distancing will not have to be breached moving forward.

Finally, the covid-19 economic shock requires economic regulation, meaning the quality of subsequent policies and regulations will be a determinant of trade in services. The post-covid structural transformation will require evidence-based policy on sectors and institutional framework matched to local digitalization contexts of AMS and the ROK, as investigated here.

Further Research

Although this study follows the nomenclature prescribed by WTO and ASEAN, assessing specific effects requires further narrowing into subsectors; for example, covid-19 instigates interest in medical and health services, which are not captured here. Further studies may also explore time-lagged digital adoption to ascertain the delayed trade effects, robustness tests for the digital adoption index to validate the results of this study, and the specific effects of sectors on stakeholders; for example, the role of ICT in MSME growth is documented in literature.

References

ASEAN integration report (2019). ASEAN Secretariat. https://asean.org/storage/2019/11/ASEAN-integration-report-2019.pdf

Asian Development Bank (2018). Building complementarity and resilience in ASEAN amid global trade uncertainty. ADB Briefs; 100 (Oct 2018). doi: 10.22617/BRF189578-2

Choi, C. (2010). The effect of the internet on service trade. Economics Letters; 109 (2): 102-104. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2010.08.005

Elding, C. and Morris, R. (2018). Digitalisation and its impact on the economy: insights from a survey of large companies. European Central Bank. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus

Hindley, B. and Smith, A. (1984). Comparative advantage and trade in services. The World Economy; 7 (4): 369-390. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9701.1984.tb00071.x

Klasen, A. (2020). The handbook of global trade policy. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Lennon, C., Mirza, D., and Nicoletti, G. (2009). Complementarity of inputs across countries in services trade. Annals of Economics and Statistics; 93/ 94 (2009): 183-205

Liu, X., Mattoo, A., Wang, Z., Wei, S. (2020). Services development and comparative advantage in manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics; 144: 1-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102438

Lim, H. (2012). Is Korea being deindustrialized? Economic Papers; 7 (1): 115-140

Lopez, J. and Ferencz, J. (2018). Digital trade and market openness. OECD Trade Policy Papers; 217. OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/1bd89c9a-en

Na, S., Bang, H., and Lee, B. (2015). A review on Korea, China and Japan’s comparative advantage in the IT services sector: Focusing on productivity analysis. KIEP World Economy Update; 5 (7): 1-6.

OECD (2017). Digitalisation: an enabling force for the next production revolution in Korea. OECD Better Policies Series; 2017. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264285545-en.pdf

The ASEAN Post (2020). How technology is changing tourism. The ASEAN Post; 25 Jul 2020. https://theaseanpost.com/article/how-technology-changing-tourism

UNCTAD (2009). Global economic crisis: Implications for trade and development. UNCTAD Secretariat Trade and Development Board. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/cicrp1_en.pdf

van der Marel, E. (2011). Determinants of comparative advantage in services [working paper]. France: Group d’Economie Mondiale. London School of Economics Research Online. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/38993

World Development Report (2016). Digital dividends. World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0728-2

World Bank (2019). Trade in services as percentage of GDP. https://data.worldbank.org/BG.GSR.NFSV

World Trade Organization (2015). Republic of Korea – Summary. Trade Policy Review; 268. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tpr_e/s268_sum_e.pdf

Yoon, C. and Kim, K. (2006). Comparative advantage of the services and manufacturing industries of Korea, China and Japan and implication of its FTA policy [working paper]. Korea Institute for International Economic Policy. https://faculty.washington.edu/karyiu/confer/seoul06/papers/yoon-kim.pdf