Digital on Digital:

Strengthening ASEAN-ROK digital-economic cooperation via integrated e-platforms

Yanminn Yong, Lee Hock Chye

School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University

Abstract

Cooperation between ASEAN and South Korea (ROK) has been accelerating since the latter’s advancement of the New Southern Policy. In particular, the digital sphere has emerged as a key area of cooperation since ROK could leverage on her technological expertise to spearhead initiatives that complement ASEAN’s digitalization agendas. As Covid-19 ushers in an era of restricted movement accompanied by contracting economies, cooperation via digital means in the economic sphere appears more pertinent than ever. This paper explores two significant facets of a digital economy which could potentially foster ASEAN-ROK digital-economic cooperation – e-commerce and business networking. Adapting to the constraints of a post-Covid-19 era, it is proffered that existing ASEAN-ROK digital cooperation in the economic field can be strengthened by establishing integrated e-platforms. With more digital initiatives building on existing ones, the shared vision of creating a “People-centered Community of Peace and Prosperity” will not reach a standstill even if the odds of Covid-19 are stacked against both ROK and ASEAN.

Introduction

South Korea’s (ROK) pivot to Southeast Asia (SEA) via the New Southern Policy (NSP) in 2017 heralded an era of increased cooperation with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Kwak, 2020). While collaboration on multiple fronts has since been forged, partnership in the digital field is especially pronounced. In particular, the latest ASEAN-ROK five-year Plan of Action repeatedly details digital partnership across multiple areas, including smart cities development, digital upskilling, smart connectivity enhancement, and many more (MOFA, 2020). It is unsurprising to witness digitalization emerging as a key area of cooperation since ROK, being a pioneer in the technological industry, has the expertise to assist ASEAN in realizing her digital agendas, as delineated in the ASEAN ICT Masterplan 2020.

Amongst the diversified forms of digital cooperation, the focus of the ASEAN-ROK digital collaboration should be centered on the economy in the near future, and its reason is twofold. Firstly, economic recovery would likely top the priority list of most countries in the post-Covid-19 phase. Economies worldwide have been severely affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, and both ROK and ASEAN are no exceptions. Not only did the Bank of Korea forecast ROK’s economic growth to shrink by 1.3% (Bank of Korea, 2020), the Asian Development Bank similarly predicted a contraction in SEA’s growth by a significant 2.7% (Asian Development Bank, 2020). However, Covid-19 has left governments with no choice but to rebuild contracting economies amidst constraints such as movement restrictions and tightened border controls. This has caused seismic shifts in the region’s digital landscape, where governments and businesses began to accelerate transition towards a digital economy (Medina, 2020). As the role of a digital economy becomes increasingly indispensable in the Covid-19 setting, cooperation in this area should be brought to the fore. Secondly, ASEAN’s potential in economic digitalization nicely complements ROK’s economic interests, begetting a win-win outcome for both stakeholders. If well developed, ASEAN’s digital economy has the potential to accelerate regional trade and local business growth, where the projected gain to ASEAN’s GDP amounts to US$1 trillion (Hoppe, May, & Lim, 2018). Partnering with an economically and digitally vibrant region would in turn better the quality of ROK’s economic diversification – a fundamental impetus of the NSP initiative (Hoang & Ong, 2020). In brief, owing to the increasing relevance of a digital economy in a post-Covid-19 era coupled by the prospects of mutual gains via economic digitalization, the development of a digital economy should definitely be considered as one of the centerpieces of ASEAN-ROK digital collaboration.

Understanding the primacy of a digital economy then begets the next question: what are the ways to strengthen ASEAN-ROK digital-economic cooperation, especially in the post-pandemic context? This paper proposes the establishment of integrated ASEAN-ROK e-platforms to meet this objective. Specifically, two aspects crucial to a digital economy – e-commerce and business networking – will be introduced to show how tailored e-platforms could foster digital-economic collaboration between ROK and ASEAN. These facets would be analyzed respectively, where we provide an evaluation of the existing initiatives, followed by proposals that outline how integrated e-platforms could enhance ASEAN-ROK digital-economic cooperation. Subsequently, we identify potential pitfalls of the proposed idea and ways to circumvent them. The paper will finally conclude by elucidating how integrated e-platforms is not only a contributor to economic digitalization per se, but is also an idea that could be conveniently transplanted to other dimensions of ASEAN-ROK digital partnership.

E-commerce

E-commerce is one of the backbones of a digital economy that generates new forms of economic growth (Kinda, 2019); both ROK and ASEAN are well-positioned to leverage on this sphere to reap economic benefits. Consistently ranked in the top tier of the Digital Opportunity Index (Ahn, 2019), ROK is home to a thriving domestic e-commerce industry. In fact, she had witnessed an exceptional 17% increase in online sale figures from 2018 to 2019 (ecommerceDB, 2020). As for ASEAN, not only did the region’s e-commerce value grow close to 700% within 4 years, industrial forecasts have also predicted this value to cross USD$150 billion by 2025 (The ASEAN Post, 2019). Hence, fostering ASEAN-ROK collaboration in this area would further expand each of their existing e-commerce sizes, increasing economic gains for both.

In addition to the salient monetary benefits, cooperation in e-commerce development is also becoming ever-more necessary as Covid-19 accelerates the transformation of business models. Many businesses were forced to do away with their brick-and-mortar stores as enforcement such as social distancing and lockdowns enact barriers to the physical sales of goods and services. This has begot a spike in business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce (WTO, 2020) where retailers, in an attempt to stay afloat, turn to e-marketplaces for alternative merchandizing means. With Covid-19 escalating business digitalization, e-commerce is set to take center stage in the post-Covid-19 era. Therefore, ROK and ASEAN should cooperate to smoothen the process of e-commerce with one another, ensuring that the ASEAN-ROK e-business potential could be maximized and make contributions to post-pandemic economic recovery.

Currently, ROK and ASEAN have in place several initiatives aimed at facilitating their respective e-commerce activities. The succeeding sub-sections would evaluate the potentiality of expanding these existing schemes’ idea to form integrated e-platforms that could promote ASEAN-ROK e-commerce.

2.1 Building on the ‘buyKorea’ initiative: ASEAN-ROK B2B2C e-marketplace

E-marketplaces are avenues where e-commerce activities materialize. Although a handful of such e-platforms is present, they have assumed a minimal role in forging ASEAN-ROK B2C or B2B e-commerce. A study by iPrice Group has divulged that ASEAN’s B2C e-commerce market share is disproportionately dominated by Alibaba’s Lazada, where the Korean e-commerce platform – 11street – claims a meagre 13% of the entire market pie (Singh, 2019). Meanwhile in ROK, the e-commerce market remains largely dominated by local players such as Coupang[1] (Millard, 2020). In each of these preferred e-marketplace, ROK and ASEAN businesses are pitched against many other non-Korean or non-ASEAN retailers who are more well-established amongst ROK and ASEAN’s respective customer base. As a result, ROK and ASEAN firms would find it difficult to substantially penetrate into each other’s e-commerce market due to their lack of brand identity and exposure.

Setting up an ASEAN-ROK e-marketplace would alleviate this problem. The e-platform could be modelled after ROK’s buyKorea initiative, which is a government-operated B2B e-platform that connects international buyers to Korean suppliers (KOTRA, 2016). By shrinking the e-commerce realm into one that is explicitly catered for Korean businesses, buyKorea concentrates the clients’ process of locating new e-commerce opportunities within the Korean market. In a similar fashion, the integrated e-marketplace is proposed to be a B2B platform that centralizes ROK and ASEAN e-commerce activities. This enables businesses to better identify potential ROK and ASEAN companies to commerce with without being overly distracted by other alternatives. The suggested e-commerce platform can even be further expanded to incorporate B2C e-transactions. This model may allow ROK and ASEAN firms to gain access to each other’s list of qualified leads[2], thereby broadening their consumer base. Moreover, as ROK and ASEAN companies increase their cooperation via B2B e-commerce, such business associations could increase their brand credibility amongst each other’s customer base, reducing the lead-time for retailers to construct brand reputation in new B2C e-markets. These advantages significantly lower the difficulty level for e-market penetration, ergo stimulating more ASEAN-ROK B2B and B2C e-commerce activities.

It is noteworthy, however, that the establishment of this integrated e-marketplace needs to be complemented by a standardized set of rules and regulations that safeguard consumer interests. As discussed during the 2016 ASEAN-Korea Workshop on E-commerce, legal mechanisms that assist the enforcement of consumer protection, e-transaction disputes resolution, and fraud detection are required (ASEAN, 2016). In this regard, ROK who has experience in instituting e-commerce industrial policies as early as 1999[3] could render constructive advice and assistance to the development of a regional e-commerce framework that provides a safe environment for ASEAN-ROK e-businesses to flourish.

2.2 Building on the ASEAN Single Window: ASEAN-ROK e-trade data platform

Additionally, e-commerce often entails the cross-border flow of goods (Ding, Huo, & Campos, 2017). As such, cooperation in terms of trade facilitation is essential in supporting international e-commerce as well. To this end, ASEAN has established the ASEAN Single Window (ASW) – a digital platform aimed at expediting the process of regional trade via electronic exchanges of commercial data and border trade-related documents (ASEAN, 2018). The integration of member states’ National Single Window (NSW) under the ASW framework has enabled companies across ASEAN to enjoy reduced paperwork formalities as well as smoother cargo and custom clearances. In the same vein, ROK and ASEAN could ameliorate their e-commerce trading by creating a common data repository that consolidates essential information from ASW and ROK’s NSW. This can be achieved by simply developing a subsidiary data platform within the ASW, where ASEAN and ROK would consolidate subsets of information that are most relevant to ASEAN-ROK trade. As trade efficacy improves due to convenient access to trade-related documents, firms would find ASEAN-ROK e-commerce increasingly viable and favorable.

A supplementary benefit to the joint development of an ASEAN-ROK e-trade data platform is the increased prospects of digital knowledge transfer. ROK’s NSW model, known as the uTradeHub, is an all-encompassing platform that provides not only e-trade infrastructure (e.g. standardized registry for electronic document), but also e-trade services (e.g. marketing, financial settlements, certification, logistics) (Yoon, 2007). Some of these efficient e-systems and digital features may be introduced into the integrated data platform to better the latter’s functionality. This confers ASEAN the chance to gain digital expertise that could improve their own ASW. The initiative can even be extended in a way where ROK collaborates with the advanced ASEAN member states to provide digital assistance to the less-developed countries who have been struggling with their operationalization of NSW (Das, 2017).

Business Networking

Networking is another important component of a digital economy that lubricates the activities of e-businesses. The catchphrase – it is not only what you know, but also who you know that matters – equally applies to the realm of e-businesses as it does to business sectors in the physical-world. Organizational and industrial-sociological scholars alike have long posited that social networking is a form of capital for firms as it provides avenues that enable the exchange of information, knowledge and resources (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Burt, 1997; Gulati, 1998), thence creating more opportunities for cooperation. The fact that the signing of an agreement between two Southeast Asia’s leading e-commerce and the Korea SMEs[4] and Startups Agency had occurred over a virtual fair aimed at networking South Korean SMEs with overseas firms (Pulse, 2020) serves only to testify the role of networking in elevating the prospects of e-business collaboration.

Networking’s boon is cognized by leaders who are responsible for spearheading ASEAN-ROK initiatives as well. Specifically, the ASEAN-Korea Centre (AKC) Secretary General, Lee Hyuk, has emphasized that priority will be placed on the creation of a ASEAN-ROK community through people-to-people exchanges (Yoon, 2019) – a key approach to accelerate cross-country networking. This agenda was further reaffirmed by President Moon Jae-in during the 2019 ASEAN-ROK Commemorative Summit, where he announced plans to introduce schemes that ease cross-border movements[5] (Asia News Network, 2019). Nonetheless, the traditional mode of networking via physical exchanges and immersion was faced with mounting challenges when governments raced to shut national borders amidst the Covid-19 outbreak. Although certain regions are gradually regaining control of the situation, the pandemic’s unpredictability, evidenced by its recurring infectious waves across Asia (Coates, 2020), makes it necessary for both the ROK and ASEAN to prepare to operate in a world of limited international movement. Hence, to ensure that e-businesses can continue to benefit from commercial networks even when restrained movement remains a characteristic of the post-Covid-19 era, new modes of networking should be explored.

Presently, existing ASEAN-ROK networking initiatives have been modified to adapt to the demographic changes in population movement caused by Covid-19. Before delving into our proposed idea, the upcoming section will review the amendment that current initiatives have undertaken to preview the type of networking that would likely take place in a post-Covid-19 era. In addition, inherent inadequacies of these initiatives would also be discussed to identify areas for improvement.

3.1 Current ASEAN-ROK Networking Initiatives

When physical distancing emerged as a new norm amidst Covid-19, the virtualization of events promptly rose to popularity. Organizers of the ASEAN-ROK networking activities have similarly jumped on the bandwagon. For instance, the recent ‘ASEAN-Korea Bio Week 2020’ and ‘ASEAN-Korea Online Contents Business Matchmaking Program’[6] were both conducted via online platforms (AKC, 2020a, 2020b). This sheds light onto the potential trajectory of future networking, that is, transforming into more digitalized forms. While one may argue that face-to-face networking can be restored if the situation stabilizes in the post-Covid-19 phase, the pandemic’s capricious nature makes it difficult to predict the feasibility of such an option. Therefore, new modes of networking in the foreseeable future is likely to manifest in digital formats.

On top of understanding the prospective nature of future networking, examining the weaknesses of current ASEAN-ROK networking discloses key areas that require amelioration. Notably, the segregation of networking spheres according to industries shrinks the opportunity set for cross-sector e-business collaboration. There are a variety of industry-specific ASEAN-ROK business networking forums at the moment, ranging from robotics to infrastructure to biotechnology (AKC, 2019). Indisputably, these networking platforms have their merits as they bring together the personnel who are most likely to create business cooperation opportunities with one another. However, this has inadvertently eliminated the chance for businesses from other sectors to build networks with the e-commerce industry, since the latter similarly has its own tailored networking arenas such as the ASEAN Digital Commerce Forum (AKC, 2018). Consequently, most of the non-e-commerce firms would be unaware of their business potential in the e-marketplaces, reducing possibilities for e-business collaboration.

Another deficiency of the current ASEAN-ROK networking approach is time constraint. Majority of the networking events are typically held over a time period of two days, with a few exceptions that last for maximum one week[7]. This suggests that there lies a limit to how much digital know-how could be transferred from larger technologically-savvy companies to smaller firms such as MSMEs[8] – the cornerstone of ASEAN’s economy that accounts for 95-99% of all business establishments (ERIA, 2019). MSMEs usually suffer from a shortage of digital technology expertise (Tan & Tang, 2016) and are definitely on the receiving end of an increasingly digitalized economy. While networking platforms host consultation sessions, the limited time frame constrains the amount of insights that could be imparted and does not ensure the continuity of digital knowledge transfers. Consequently, digital divide between large and small firms remains largely unbridged[9], impeding the creation of more e-business opportunities amongst the MSMEs.

3.2 ASEAN-ROK social business e-networking Platform (SBEP)

Since uncertainties over movement restrictions abound in a post-Covid-19 era, migrating networking activities into the virtual space via the establishment of an ASEAN-ROK social business e-networking platform is a suitable alternative. The SBEP is suggested to serve as a multilateral networking avenue where ASEAN and ROK firms could create intra and inter-sector business networks. With personalized profiles that cover a range of basic business information[10], users will be granted access to other industries’ e-networking pages to seek potential cross-sector e-business collaboration. This is particularly crucial as securing networks with the digital technology industry is becoming more of a necessity for many businesses who were forced to digitalize amidst Covid-19. The tourism sector, for example, was one of the most badly hit industries that needs to accelerate their pace of digitalization. Recognizing this urgency, the AKC has even organized a webinar aimed at boosting ASEAN-ROK smart tourism businesses (AKC, 2020). Nonetheless, on top of such intra-sector initiatives, cooperative ties with the ICT and e-commerce industries are also vital to developing a smart tourism ecosystem (Fereidouni & Alizadeh, 2020). The SBEP thus aims to become a one-stop destination where ROK and ASEAN firms could network with different industries to optimize e-business cooperation opportunities.

Additionally, the amount of networking time available on the SBEP is infinite since it is a 24/7 functioning e-service. This means that there is ample time for information sharing, so long as the ASEAN-ROK firms arrive at an agreement to do so. Hence, the SBEP is proposed to adopt social media features that facilitate online communication between ASEAN-ROK companies. This encompasses functions such as secured chat rooms, video conferences, and convenient document uploading processes. Leading in both the e-commerce and technology industries, ROK is abundant in digitally-competent companies who could assist the region’s MSMEs to climb the ladder of digitalization. The availability of virtual communication channels coupled with the absence of time constraint would create more opportunities for the diffusion of digital insights as well as collaborative innovation, thereby alleviating the severity of digital gap between large and small firms. In coordinating the transmission of digital knowledge, SBEP complements the goal to “empower MSMEs by promoting and accelerating the use of digital technology”[11]. As the community of digitally-abled companies balloons in size, ASEAN-ROK e-businesses is poised to increase.

Indeed, one may question the necessity of an integrated SBEP since there exist many other business networking sites that can help firms connect on a global scale. However, many of such platforms have algorithms that may sieve out ASEAN and ROK businesses from each other’s potential connection list. LinkedIn, for example, builds business networks by analyzing users’ working location, existing connections, and profile content (Jurka, 2018). Since the user profile information of ASEAN and ROK firms would likely correlate more to other companies of their own region, the algorithms may not effectively interlink ROK-ASEAN businesses together. Thus, analogous to the rationale of an integrated e-marketplace, the SBEP aims to create a concentrated social circle where ASEAN and ROK firms could network with each other despite having no prior associations.

Potential Limitations and Proposed Solutions

Despite its potentiality, there are a few challenges to the implementation of integrated ASEAN-ROK e-platforms. With regards to the e-trade data platform in particular, data security issues and the paucity of infrastructures are potential hindrances. For the former, cross-border data flows would necessitate not just intra-ASEAN but also ASEAN-ROK cooperation on the harmonization of legal landscapes for data protection purposes. One possible means to fulfil this agenda is to incorporate ROK into the development of the 2018 ASEAN Framework on Digital Data Governance (ASEAN, 2018). For the latter, data centers and cloud computing services are fundamental facilities required to support the voluminous data and e-documentations from ASEAN and ROK firms. While this might not necessarily be a concern for ROK and certain ASEAN members[12], it remains a real obstacle amongst the less digitally-advanced CLM[13] states. Hence, more effort is needed to assist these states in their development of the requisite infrastructures. This can be achieved by promoting greater CLM-ROK information technology collaboration; the recent cooperation between ROK and Thailand’s telecommunications companies in the construction of a data center facility (Sharon, 2020) could serve as a precedent for ROK-led digital infrastructure projects in the CLM states.

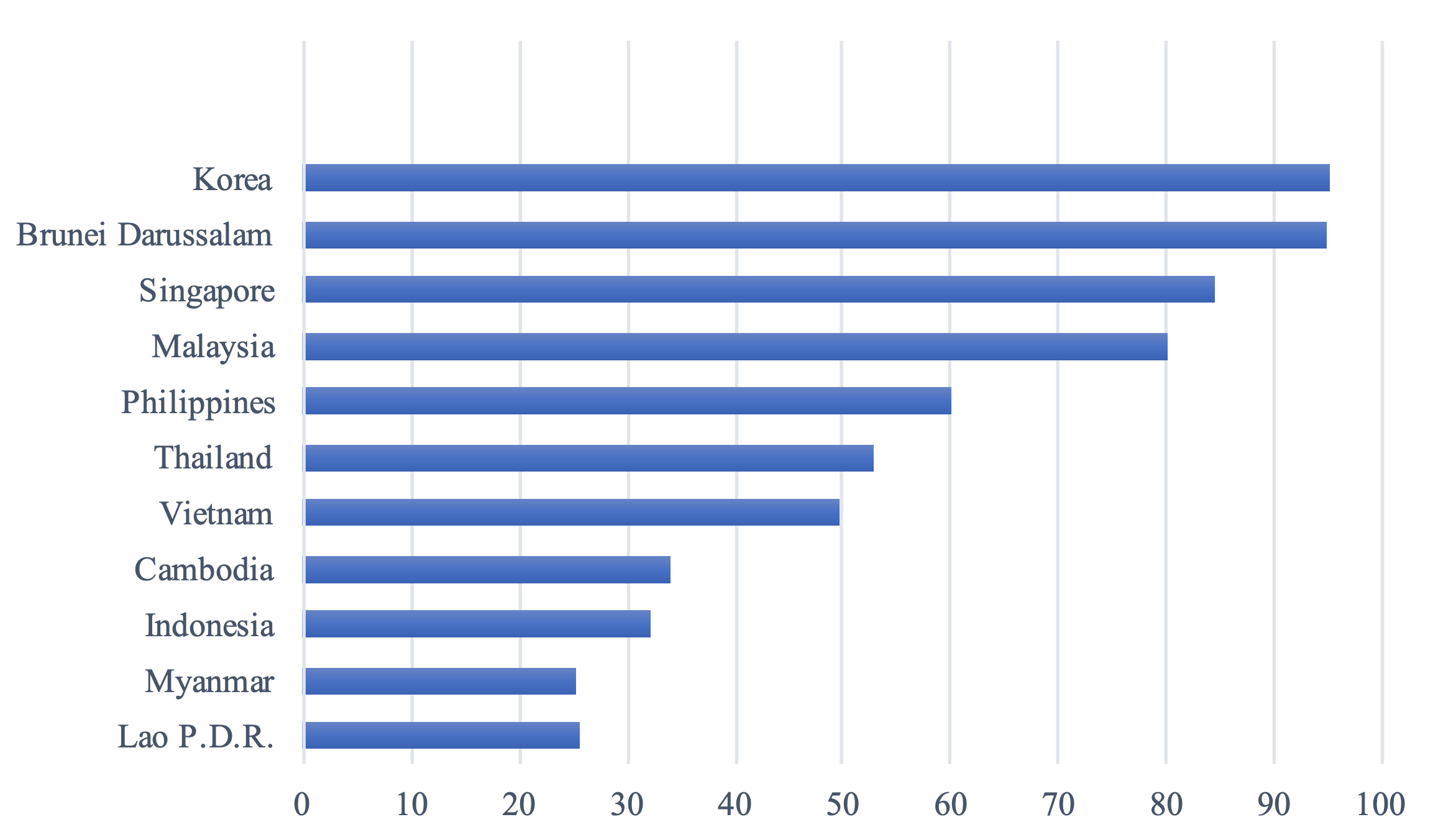

As for the SBEP, accessibility issues may arise due to low internet and broadband penetration. Within ASEAN lies a large digital divide, where more than 70% of people in Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos and Myanmar remain offline (Figure 1). In order to ensure comprehensive access to platforms like SBEP, developments in ICT infrastructure have to be accelerated. ROK and ASEAN could step up their joint commitment in realizing ICT-relevant objectives in the ASEAN Digital Master Plan such as broadband deployment and improvement in broadband affordability (ASEAN Secretariat, 2015). This process of infrastructural development, however, requires time to be brought to fruition. A short-term resolution that could enable business operators from less-developed countries to stay connected to the e-platform is the creation of an online/offline SBEP mobile application. This is because mobile phone penetration is consistently high across all ASEAN member states, where its density is estimated at 967 per 1000 population (ASEAN, 2018). This implies that the SBEP mobile application would be accessible by individuals who reside in places that lack well-established broadband connection as well. As a matter of fact, some scholars have already postulated a similar idea, suggesting an extension of agricultural-related mobile applications to include offline functions; this is to ensure that farmers with mobile phones could continue to reap benefits of technological systems even when their environment is ill-equipped with the required infrastructure (Bartling et al., 2016).

Notwithstanding the digital barrier, SBEP remains a viable option as its social media style caters to the large social site user base in ROK and ASEAN. Not only has ROK’s social media penetration rate reached an impressive 87% (Shim, 2020), social media usage in the Southeast Asia region is experiencing phenomenal growth as well (World Bank, 2019). This indicates that most people in ASEAN and ROK would be promptly attuned to utilizing SBEP for business networking. In sum, enhancement in other digital areas have to be concurrently carried through to support the e-platforms in engendering more digital-economic collaboration.

Figure 1: Percentage of individuals using the internet in ASEAN member states and ROK

Source: Measuring the Information Society Report 2018, International Telecommunication Union

Conclusion

Efforts aimed at realizing the ASEAN-ROK’s vision of building a “People-centered Community of Peace and Prosperity” are set to unfold in an era of digitalization. As Covid-19 continues to catalyze the pace of Fourth Industrial Revolution, ROK and ASEAN could further enhance digital collaboration to better each other’s adaptability to the dynamics of a rapidly shifting digital landscape. This paper argues that digital-economic cooperation should be at the forefront of ASEAN-ROK’s agenda list; the main reason being that a robust digital economy would greatly aid countries to tide over pandemic-triggered economic downturns. In line with this proposition, two important aspects of a digital economy – e-commerce and business networking – have been examined in detail to unearth potential means to strengthen ASEAN-ROK digital-economic cooperation.

It is proffered that tailored integrated e-platforms are useful drivers of digital-economic collaboration between ROK and ASEAN. In the case of encouraging more ASEAN-ROK e-commerce activities, whilst an integrated e-marketplace would assist ROK and ASEAN firms to penetrate into each other’s e-commerce market with greater ease, a common e-trade data platform stands to benefit e-commerce retailers by simplifying ASEAN-ROK cross-border trade operations. With respect to promoting ASEAN-ROK business networking, the SBEP serves as an avenue for extensive inter and intra-industrial networking, as well as timeless information sharing amongst firms of various sizes. Even if border or movement restrictions were to persist in the post-covid-19 phase, installing these e-platforms would ensure the continuity and even strengthen ASEAN-ROK cooperation in the e-business realm, thereby contributing to the construction of a sustainable digital economy.

What is more interesting about the idea of integrated e-platforms is its flexibility in being applied to other aspects of ASEAN-ROK digital cooperation. For instance, the e-trade data platform could be modified into one that assembles educational materials, complementing existing ASEAN-ROK e-learning initiatives such as the ASEAN Cyber University. Social networking e-platforms could be also established for ASEAN-ROK academics where a whole range of ideas could be exchanged and debated, including those that are constructive to digital innovation. It is almost safe to say that there is no exhaustive list concerning the types of e-platforms that could be designed to buttress ASEAN-ROK digital cooperation; what is left to do is to identify optimal e-platform versions that best meet the needs of the different digital projects. As digitalization becomes the new normal, developing new digital initiatives such as integrated e-platforms would fortify and enhance existing digital efforts. Perhaps, the only way forward is digital on digital.

References

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S.-W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17-40.

Ahn, C. (2019, January/February). E-commerce & ICT Development in South Korea: Prospects & Challenges. Japan SPOTLIGHT, 18-23.

ASEAN. (2016, September 14). ASEAN, Korea to build trust and confidence in e-commerce. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from ASEAN: https://asean.org/asean-korea-to-build-trust-and-confidence-in-e-commerce/

ASEAN. 2018. E-ASEAN Connecting to grow. Accessed 10 28, 2020. http://investasean.asean.org/index.php/page/view/e-asean.

ASEAN. (2018). Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Framework on Digital Data Governance: https://asean.org/storage/2012/05/6B-ASEAN-Framework-on-Digital-Data-Governance_Endorsed.pdf

ASEAN. (2018). ASEAN Single Window. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from ASEAN: https://asw.asean.org/

ASEAN Secretariat. (2015). The ASEAN ICT Masterplan 2020. ASEAN.

ASEAN-Korea Centre (AKC). (2018, 7 25). Centre Activities. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from 2018 ASEAN Digital Commerce Forum: aseankorea.org/eng/Activities/activities_view.asp?BOA_NUM=13074&BOA_GUBUN=99

ASEAN-Korea Centre (AKC). (2019, 6 7). 2019 ASEAN-Korea Centre Brochure. Seoul, South Korea.

ASEAN-Korea Centre (AKC). (2020, 9 3). News & Media. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from ASEAN and Korean tourism industries highlight smart tourism amid COVID-19: https://www.aseankorea.org/eng/New_Media/press_view.asp?page=1&BOA_GUBUN=10&BOA_NUM=15612

ASEAN-Korea Centre (AKC). (2020a, 8 14). Centre Activities. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from ASEAN-Korea Online Contents Business Matchmaking Program: https://www.aseankorea.org/eng/Activities/activities_view.asp?page=1&BOA_GUBUN=99&BOA_NUM=15579

ASEAN-Korea Centre (AKC). (2020b, 9 21). News & Media. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from ASEAN and Korean biotech companies seek greater cooperation amid the COVID-19 pandemic: https://www.aseankorea.org/eng/New_Media/press_view.asp?page=1&s_date=MONTH&s_range=ALL&S_ALLTEXT=online&BOA_GUBUN=10&BOA_NUM=15688

Asia News Network. (2019, 11 18). Asia News Network. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Coming challenges call for stronger Korea-ASEAN ties: https://asianews.network/2019/11/18/coming-challenges-call-for-stronger-korea-asean-ties/

Asian Development Bank. (2020, 6). Lockdown, loosening and Asia’s growth prospects. Asian Development Outlook Supplement, p. 12.

Bank of Korea. (2020). Economic Statistics System. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Korean Stat 100: http://ecos.bok.or.kr/jsp/vis/keystat/index_e.html#/detail

Bartling, Mona, Anton Eitzinger, Steven Sotelo, and Karl Atzmanstorfer. 2016. “Press the Button: Online/Offline Mobile Applications in an Agricultural Context.” GI_Forum 1: 106-116.

Burt, R. S. (1997). The contingent value of social capital. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(2), 339–365.

Coates, S. (2020, 7 27). The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Asia battles second wave of coronavirus with fresh lockdowns: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/07/27/asia-battles-second-wave-of-coronavirus-with-fresh-lockdowns.html

Das, S. (2017). ASEAN Single Window: Advancing Trade Facilitation for Regional Integration. Perspective, 72, 1-7. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ISEAS_Perspective_2017_72.pdf

Datacentrepricing. (2020). The Cloud and Data Centre Markets in the Asia Pacific Region. Tariff Consultancy Ltd.

Ding, F., Huo, J., & Campos, J. K. (2017). The development of cross border e-commerce. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 37, 370-383.

ecommerceDB. (2020). The eCommerce market in South Korea. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from ecommerceDB: https://ecommercedb.com/en/markets/kr/all

Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA). (2019). Study on MSMEs Participation in the Digital Economy in ASEAN.

Fereidouni, M. A., & Alizadeh, H. N. (2020). An Integrated E-commerce Platform for the ASEAN Tourism Industry: A Smart Tourism Model Approach. In L. Chen, & F. Kimura (Eds.), E-commerce Connectivity in ASEAN. Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

Gulati, R. (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 293–317.

Hoang, T. H., & Ong, G. (2020, 1 30). Assessing the ROK’s New Southern Policy towards ASEAN. ISEAS Perspective(7).

Hoppe, F., May, T., & Lim, J. (2018). Advancing towards ASEAN digital integration. Bain & Company, Inc.

International Telecommunication Union. (2018). Measuring the Information Society Report: Volume 2. ICT Country profiles. Geneva: ITU Publications.

Ironpaper. (2019, 1 29). Insights. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from What is a Qualified Lead? How to Set Criteria: https://www.ironpaper.com/webintel/articles/what-is-a-qualified-lead-how-to-set-criteria/#:~:text=A%20qualified%20lead%20is%20someone,is%20unique%20to%20your%20business.

Jayaraman, P. (2017, 9 26). The ASEAN Post. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Data centres are booming in Southeast Asia: https://theaseanpost.com/article/data-centres-are-booming-southeast-asia

Jurka, T. (2018, 3 29). Linkedin Engineering. Retrieved from A Look Behind the AI that Powers LinkedIn’s Feed: Sifting through Billions of Conversations to Create Personalized News Feeds for Hundreds of Millions of Members: https://engineering.linkedin.com/blog/2018/03/a-look-behind-the-ai-that-powers-linkedins-feed–sifting-through

Kinda, T. (2019, 7). E-commerce as a Potential New Engine for Growth in Asia. IMF Working Paper, p. 28.

Korea Trade Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA). (2016). Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Intro to B2B e-market place: https://www.kotra.or.kr/foreign/biz/KHENKO020M.html

Kwak, S. (2020, 1 7). The Asan Forum: National Commentaries. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from A View from South Korea: http://www.theasanforum.org/a-view-from-south-korea-3/

Medina, A. F. (2020, 9 15). ASEAN Briefing. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Investing in ASEAN’s Digital Landscape: New Opportunities After COVID-19: https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/investing-in-aseans-digital-landscape-new-opportunities-after-covid-19/

Millard, N. (2020, 4 9). Korea’s ecommerce market is still dominated by local players. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from TechinAsia: https://www.techinasia.com/korea-ecommerce-dominate-local-players#:~:text=Perhaps%20best%20known%20for%20K,it’s%20dominated%20by%20local%20players.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of Korea (MOFA). (2020, 9 10). Mission of the Republic of Korea to ASEAN: ASEAN Meetings. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from ASEAN-Republic of Korea Plan of Action to Implement the Joint Vision Statement for Peace, Prosperity and Partnership (2021-2025): http://overseas.mofa.go.kr/asean-en/brd/m_20164/view.do?seq=759758&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&multi_itm_seq=0&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&company_cd=&company_nm=

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). OECD Economic Surveys: Korea. Economic and Development Review Committee.

Palmer, A. (2020, June 16). Coupang, a SoftBank-backed start-up, is crushing Amazon to become South Korea’s biggest online retailer. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from CNBC: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/16/coupang-crushed-amazon-to-become-south-koreas-biggest-online-retailer.html

Pulse. (2020, 6 17). Maell Business News Korea. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Southeast Asia’s two e-commerce giants to market South Korean products: https://pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?year=2020&no=620851

Sharon, A. (2020, 10 17). Open Gov Asia. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Thailand’s new data centre to be built by Korean teleco: https://opengovasia.com/thailands-new-data-centre-to-be-built-by-korean-teleco/

Shim, W.-h. (2020, 9 7). The Korea Herald. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Korea’s social media penetration rate ranks third in world: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200907000815

Singh, P. (2019, January 25). Lazada leads the E-commerce Battle in Southeast Asia. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Entrepreneur Asia Pacific: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/326915

Tan, K. S., & Tang, J. (2016). New skills at work: Managing skills challenges in ASEAN-5. Research Collection School Of Economics.

The ASEAN Post. (2019, October 22). E-commerce spending expected to triple in ASEAN. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from The ASEAN Post: https://theaseanpost.com/article/e-commerce-spending-expected-triple-asean

World Bank. (2019). The Digital Economy in Southeast Asia: Strengthening the Foundations for Future Growth. World Bank, Information and Communications for Development. Washington, D.C: World Bank.

World Trade Organization (WTO). (2020). E-Commerce, Trade and the Covid-19 Pandemic. Economic Research and Analysis. World Trade Organization.

Yoon, S. (2019, 10 8). KOREA.net. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from ‘People are the top priority in Korean-ASEAN cooperation’: http://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/People/view?articleId=175923

Yoon, S. J. (2007, 8 14). Korea’s National Single Window Platform for paperless trade and e-logistics. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from Symposium on Paperless Trading Capacity Building and Intellectual Property Rights Protection Beijing, China: http://mddb.apec.org/documents/2007/ecsg/sym1/07_ecsg_sym1_003.pdf

Yu, M. (2002). South Korea – Overseas Duty Visit by the Panel on Information Technology and Broadcasting. Legislative Council Secretariat. Retrieved 28 October, 2020 from https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr01-02/english/sec/library/0102in20e.pdf

[1] A domestic e-commerce giant that supplanted Amazon as the top online retailer in ROK within a span of 10 years (Palmer, 2020).

[2] Qualified leads refer to individuals who could potentially become a firm’s customer, based on the criteria and personal information they have provided (Ironpaper, 2019).

[3] In 1999, the Basic Act on Electronic Commerce was established in ROK. Subsequently in 2000 and 2001, the “Comprehensive Policies for e-Commerce Development” and “e-Business Initiative in Korea” were implemented (Yu, 2002).

[4] SMEs is the abbreviation for Small and medium enterprises.

[5] Examples include streamlining of visa issuance procedures and open-skies policy.

[6] Business networking events that were organized by the AKC for the biotechnological industry and the various contents sector respectively.

[7] Refer to the ASEAN-Korea Centre’s ‘Centre Activities’ website for the duration of each networking events.

[8] MSMEs is the abbreviation for Micro, small & medium enterprises.

[9] According to a study by Bain & Co, only a meagre 16% of MSMEs in ASEAN use digital technologies to their full potential (Hoppe, May, & Lim, 2018). Even within ROK itself, digital gaps between large and small firms remain wide (OECD, 2020).

[10] Examples of such information details include business type, description of the firm’s products and services, as well as investment interests.

[11] An objective that was listed in the ASEAN-ROK five-year Plan of Action (2021-2025) (MOFA, 2020).

[12] According to Datacentrepricing’s new report, ROK, Vietnam and Thailand are amongst the list of countries whose data center markets are forecasted to experience high growth rates (Datacentrepricing, 2020). Several ASEAN member states such as Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand have also been channeling investments into data center infrastructures in their respective countries (Jayaraman, 2017). It is thus likely that these states would be well-equipped to accommodate the integrated data platform.

[13] CLM is the abbreviation for Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.