Calista Chong

University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Abstract

COVID has fundamentally changed our world. Amidst the uncertainty, one thing is for certain – our dependence on digital technologies will exponentially increase in future. The World Economic Forum (2018) estimates that the ASEAN digital economy will add US$1 trillion to regional GDP over the next decade, and the ROK has carved new frontiers in digital and artificial intelligence technology and established itself as a pioneer in 5G technology. This paper seeks to present insights on the future of ASEAN-ROK digital cooperation and is organised into five sections.

The first section explores the economic and strategic rationale behind ASEAN-ROK digital cooperation and concludes that it is fruitful for both middle powers to cooperate in the digital sphere, as they are close trading partners with shared interests in mitigating the consequences of Sino-American rivalry. The second section surveys the digital landscape of the eleven countries with reference to the 2019 Cisco Digital Readiness Index and asserts that there are digital disparities within ASEAN and between both partners too, thus necessitating the need for an inclusive ASEAN-ROK blueprint that reflects the digital priorities of all parties involved. The third section outlines existing digital initiatives between ASEAN and the ROK. The penultimate section will analyse the opportunities and challenges that have arisen from COVID-19. This paper argues that while the pandemic has devastated our economy and exposed the digital divide between segments of society, it has alerted us to the significance of digital governance, resilient supply chains, digital literacy, and new growth sectors, such as telehealth and social media technology.

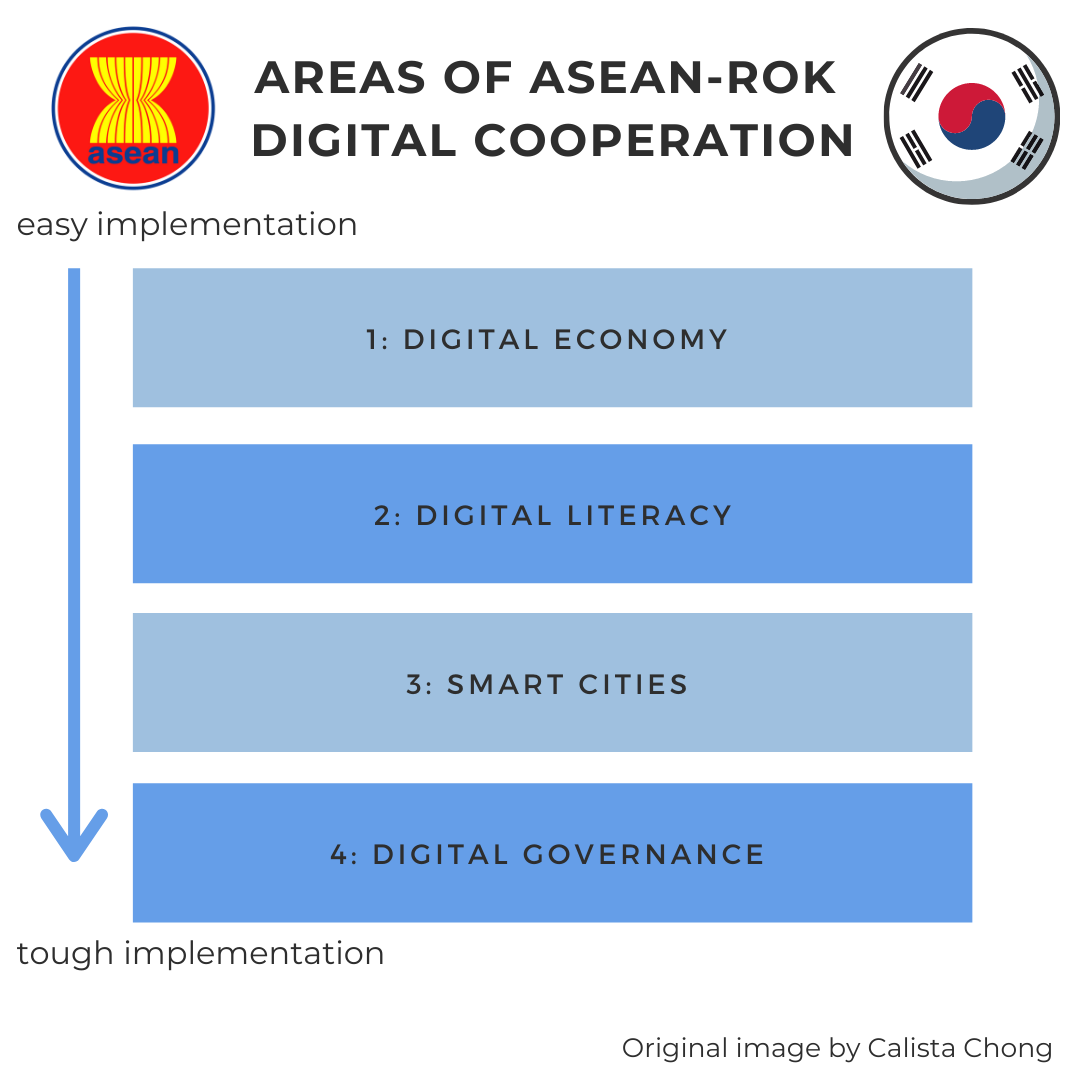

Last but hardly the least, this paper proposes four areas of ASEAN-ROK digital cooperation – developing the digital economy by leveraging the momentum in high-growth sectors; fostering digital inclusion by increasing digital literacy and encouraging the co-creation of teaching resources; building smart cities by nurturing climate-resilient urban solutions through developmental mentoring and training opportunities; and digitising the delivery of public services through regular intergovernmental dialogue and mutual assistance. A fruitful partnership in these respects will allow ASEAN-ROK bilateral relations to grow from strength to strength.

Introduction

COVID-19 has brought about change in a volatile world that has been riven by the US-China geopolitical rivalry and revolutionised by the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). ASEAN and the Republic of Korea (ROK) are no strangers to these phenomena, and both parties will find it mutually beneficial to broaden and deepen their digital cooperation in the post-COVID era. Having launched the New Southern Policy 2.0 this year, it is also the ROK’s foreign policy imperative to translate its vision of ASEAN-Korea engagement into action.

This paper is org anised into five sections. Section 1 explores the economic and strategic rationale behind digital cooperation; Section 2 examines the digital disparities within ASEAN and between ASEAN and the ROK; Section 3 takes stock of existing digital cooperation between both parties; Section 4 evaluates the opportunities and challenges that arise from the pandemic; and Section 5 proposes four areas of digital cooperation – digital economy, digital inclusion, smart cities and digital governance – sequenced according to the ease of implementation.

I. What’s In It For Us: Benefits of ASEAN-Korea Digital Cooperation

The 2019 ASEAN-Korea Commemorative Summit celebrated a significant diplomatic milestone that reflects the strong relationship between ASEAN and the ROK for the past thirty years. President Moon’s New Southern Policy (NSP), which was unveiled in 2017, is ‘novel in its level of enthusiasm and commitment’ towards Southeast Asia, and the recent expansion of NSP reiterates the significance of a strategic partnership between both parties (Wongi, 2019). At the summit, the ROK and ASEAN leaders have not only affirmed their commitment to existing collaborations, but also agreed on the need to forge more extensive partnerships in areas like ‘4IR, fintech, smart cities and digital industries’.

ASEAN-Korea digital cooperation has the potential to be exceptionally fruitful and constructive. Firstly, there is a compelling economic case to be made for digital cooperation, as there exists strong economic interdependence between both parties. ASEAN is the ROK’s second largest trading partner after China. In 2019, the combined exports of ASEAN member states reached US$80 billion from January to October, and have soared twenty-fold compared to the 1980s (Yonhap News, 2019). Similarly, the ROK is the fifth largest trading partner of ASEAN and accounts for 5.7% of its total trade in 2018 (ASEAN Studies Centre et al., 2019). Moreover, the World Economic Forum (2018) estimates that the ASEAN digital economy will add US$1 trillion to regional GDP over the next decade. A digitally and financially literate ASEAN population will spur economic growth in all eleven countries.

Secondly, digital cooperation is immensely important to fulfilling both parties’ strategic objectives. In a time where ASEAN is wary of being caught in the Sino-American technological competition, the ROK could fill the lacuna as a valuable partner in improving ASEAN’s digital infrastructure as a fellow middle power with ‘no hegemonic intentions and designs’ in the region (Hoo, 2019). Likewise, ASEAN is central to the ROK’s ‘hedging efforts’ in a highly bipolar regional environment, and offers a desirable platform on which regional architecture can be built, such as ASEAN-led multilateral mechanisms like the East Asian Summit or ASEAN-Plus-Three (Wongi, 2019). This highlights that digital partnerships can lay a strong foundation for the fulfilment of politico-security objectives. For the above reasons, digital cooperation between ASEAN and Korea holds great promise.

II. Tracking Digital Transformation across ASEAN and Korea

ASEAN is a highly diverse region, boasting a variety of political systems, languages, and cultures. Its diversity is also reflected in the unevenness of digital development among ASEAN states – by extension, these digital disparities are present between ASEAN and South Korea too.

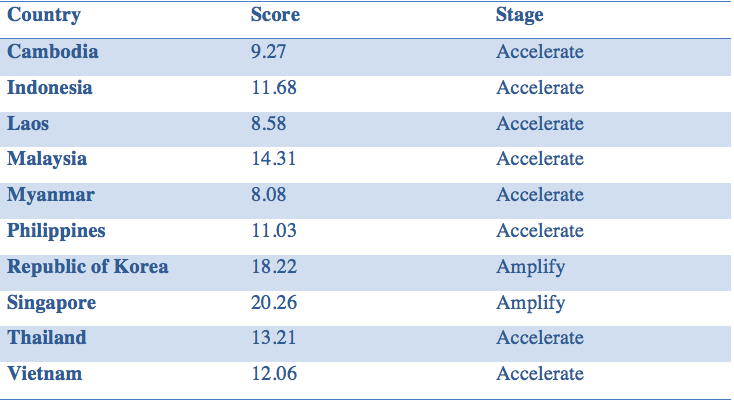

The Cisco Digital Readiness Index (2019) has been chosen to illustrate this point, as it is a reputable index and includes the ROK and most ASEAN member states in its study, with the exception of Brunei. From seven components, a standardised index is constructed with a maximum possible score of 25. Countries are grouped into three stages of digital readiness based on their score – Activate, Accelerate, Amplify – where ‘Activate’ countries are in the earliest stages of their digital journey; ‘Accelerate’ countries had taken some steps forward and have further opportunities to improve in digital readiness; and ‘Amplify’ countries have taken bold steps in digitalisation. The table (Fig. 1) below reflects the digital readiness scores of 9 ASEAN members and the ROK. In the index, Singapore ranked 1st place, while Myanmar is ranked 111th out of 141 countries. As ASEAN-Korea digital cooperation gains momentum in the next decade, nations should ensure that each member’s digitalisation priorities are accommodated within an inclusive ASEAN-Korea digital blueprint.

Fig. 1: Table with the CISCO Digital Readiness scores of ASEAN (with the exception of Brunei) and the Republic of Korea (Source: CISCO Digital Readiness Index 2019)

III. Taking Stock of ASEAN-Korea Digital Cooperation

ASEAN and the ROK have partnered on a plethora of digital and technological initiatives. Firstly, the ASEAN-Korea Business Council, created to increase SMEs’ competitiveness, has been tasked with guiding the transformation of ASEAN to a digital-driven economy, preparing its people for technological developments in emerging industry sectors. The ROK has contributed towards the Knowledge Sharing Programme (2018-19) that strengthened IP infrastructure in ASEAN, and also shared best practices in agricultural machinery and food processing through Technology Advice and Solutions from Korea (TASK) (CMB ASEAN Research Institute [CARI], 2020). Furthermore, the ROK has supported ASEAN’s Smart Cities Network (ASCN) in promoting smart and sustainable urban development. At the ASEAN-Korea Startup Summit in November 2019, President Moon also pledged to establish a start-up policy roadmap to facilitate innovation and entrepreneurship. At the ASEAN+3 Summit in April 2020, the ROK’s mission to ASEAN launched a joint programme, ‘Enhancing the Detection Capacity for COVID-19 in ASEAN Countries’ that provided ASEAN states with test kits, PCR equipment and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) (ASEAN, 2020).

There is much to look forward to in the future. The ASEAN-Korea Plan of Action (2021-25) adopted this year affirmed the possibility of establishing an ASEAN-Korea Standardisation Joint Research Centre and Industrial Innovation Centre to respond to the challenges of the 4IR. The ROK has also vowed to support the implementation of the ASEAN Digital Master Plan (ADMP) 2025 to build an ASEAN-Korea digital ecosystem, strengthening other fields in the digital economy, including e-government and digital literacy (ASEAN, 2020).

IV. Opportunities and Challenges Presented by COVID-19

Social distancing in the pandemic has made the world recognise its dependence on digital tools. What are some of the challenges and opportunities that have emerged from the pandemic?

Firstly, COVID-19 has exposed the vulnerability of global supply chains by disrupting the mobility of people and goods. ASEAN manufacturers saw the ‘worst month on record’ in March 2020, with the headline PMI falling from 50.2 to 43.4 (CARI, 2020). Many industries across ASEAN have been affected by supply chain disruptions linked to China. Tech firms in Penang, Malaysia rely on China for nearly 60% of components and materials that they supply to major tech multinationals, textile firms in Cambodia and Vietnam procures 60% of its textiles from China, and Indonesian factories obtain 20% to 50% of its raw materials from China alone (CARI, 2020). The ROK’s economy is projected to contract 1% in 2020 – while this makes the ROK one of the best-performing economies this year, it will still be the ROK’s worst economic performance since 1998 (Kim, 2020).

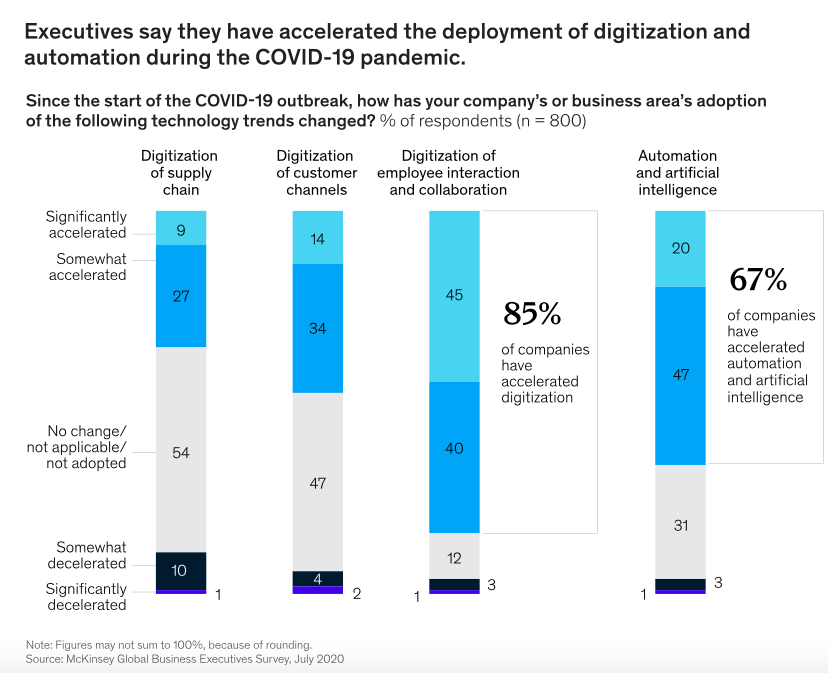

While COVID-19 has brought economic shocks in the immediate term, it presents opportunities to harness digital technologies to strengthen the resilience of ASEAN and the ROK’s supply chains. According to a global McKinsey survey in July 2020, 35% of surveyed firms have further digitised their supply chains and 67% of firms have accelerated their adoption of automation technologies (Figure 2) (McKinsey, 2020).

Figure 2: Results from the McKinsey Global Business Executives Survey, July 2020

Firms could use 3D printing as a substitute for the physical transfer of goods, and AI-powered wearables could help workers maintain social distancing in production plants (Williamson, 2020). Blockchain technology rebuilds disrupted trade networks by quickly verifying a particular exchange of value, building trust between suppliers and consumers (World Economic Forum, 2020).

Secondly, COVID-19 also threatens to enlarge the digital divide, which the UNESCAP calls the ‘new face of inequality’. This problem is two-fold. On one hand, there is a shortage of digital supply – rural areas lack fibre optic infrastructure and broadband connectivity. Moreover, the lack of digital literacy has led to a weak demand for digital services too. As a result, micro- and small enterprises find it difficult to transition to a digital business model, and students are deprived of access to remote learning. This has severe implications for economic recovery and the long-term development of human capital. Thus, a two-pronged approach to digital inclusion that increases both digital demand and supply is a key priority for ASEAN-Korea cooperation in the post-COVID era.

Thirdly, COVID-19 has also unveiled scalable digital opportunities such as telecommuting, e-commerce and telemedicine. Remote working, a relatively rare phenomenon in ASEAN, has become the new norm. Deloitte (2020) estimates that 50 million jobs could switch to remote work across ASEAN-6 countries. Telehealth offerings have also been popular in ASEAN, revolutionising the integration of ICT into healthcare. Traffic on e-commerce platforms have risen and Southeast Asia’s Internet economy is valued at US$100 billion in 2019, which is expected to rise to US$300 billion by 2025 (Medina, 2020). Thus, ASEAN-Korea cooperation should be focused on leveraging these promising sectors to propel growth in the post-COVID era.

Lastly, COVID-19 has arguably posed the biggest test of the governments’ mettle in recent years. Afflicted by a public health crisis and unemployment on an unprecedented scale, effective leadership is of the essence at this critical juncture. While digital technology is not a panacea, its strategic application contributes to a nimble national strategy for combating COVID-19. The ROK and Singapore have effectively utilised geospatial data in containing the epidemiological outbreak and delivering public services remotely. There is great potential for intergovernmental collaboration in the transition to digital governance and smart cities to improve on crisis management in future.

Although the pandemic has brought devastating shocks to the economy and exposed the digital divide between segments of society, it has alerted us to the significance of resilient supply chains, digital literacy, emerging growth sectors and digital governance. Leveraging these opportunities will enable ASEAN and the ROK to make a successful rebound after the brief period of disorientation.

V. Areas of ASEAN-Korea Digital Cooperation

This paper proposes four areas of digital cooperation between ASEAN and the ROK. While the ease-benefit matrix[1] is used as a common tool for evaluating and prioritising decisions, impact measurement of the proposed policies involves complex variables that cannot be satisfactorily explored within the scope of this paper. Therefore, the four action areas will be sequenced according to their ease of implementation, which is approximated by the level of political will and estimated economic cost (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Four areas of ASEAN-Korea digital cooperation

Figure 4 presents a graphical illustration of the key recommendations that this paper will explore in the following pages.

Figure 4: Summary of Proposed Solutions

Digital Dollars: Enhancing Economic Cooperation in the Digital Age

The paper first explores ASEAN-Korea cooperation on the digital economy because it is arguably the easiest area of collaboration owing to strong political will, economic interests and relatively low upfront costs.

The New Southern Policy is underpinned by a strong economic imperative, and as illustrated above, the ROK and ASEAN states enjoy close economic interdependence. This paper suggests that ASEAN and the ROK should deepen digital and technological cooperation in emerging growth sectors. New practices have emerged to address the demand for essential services – not least healthcare. Remote health monitoring and cheaper access to medical consultations for non-critical patients will alleviate the pressure on limited health facilities and medical supplies in a burgeoning public health crisis. The global digital health market is projected to reach US$510.4 billion by 2025, and the Asia-Pacific region will witness the highest market growth in the forecasted period (VynZ Research, 2020).

We have seen commendable initiative from the private sector. The demand for Indonesia’s telehealth firms, such as Halodoc and Alodokter, has skyrocketed in 2020 (Nortajuddin, 2020). While the ROK has faced resistance in telehealth implementation from pressure groups, the government has suggested that it will ‘positively consider introducing the telemedicine system’ given its convenience and effectiveness in the COVID era (The Korean Herald, 2020). Therefore, this paper suggests that countries could design initiatives to support e-Health innovation or hold a joint forum to address challenges in telehealth implementation. This can take the form of an ASEAN-Korea innovation challenge modelled after USAID’s annual Mobile Solutions Forum. Alternatively, telehealth companies can be invited to present at future iterations of the ASEAN-Korea Innovation Showcase, first started in 2019.

Digital consumer services also present a promising area of collaboration. The region has seen a rise in ‘super-apps’, which provide various services under a single umbrella. The ROK is one of the few countries in the world that has retained loyalty to home-grown social media and communication apps – KakaoTalk is the most popular application in the ROK, while Naver captures more than 70% of the Korean search engine market share (Chapco-Wade, 2018). Other businesses in the region have achieved similarly astounding success. Grab and Gojek are ride-sharing firms that have acquired ‘super-app’ status for offering additional services like GrabFood and GoClean respectively. Such super-apps highlight the value of building an integrated digital ecosystem in which mutual learning can occur. This paper suggests that a cross-fertilisation of digital technologies between the conglomerates in ASEAN and the ROK would be beneficial and they should be regarded as important partners in the development of an ASEAN-Korea digital ecosystem.

In short, cooperation in the digital economy is well under way due to strong political will and an appetite for innovation in digital technologies. The ROK and ASEAN should leverage on the momentum in emerging sectors like telehealth and digital consumer services to secure future prosperity.

Bridging the Digital Divide: Increasing Demand and Supply for Digitalisation

Urban-Rural Digital Divide

In Southeast Asia, urbanisation rates are as low as 23.81% in Cambodia and 36.63% in Vietnam as of 2019 (Statista, 2019). Moreover, as a result of COVID-19, millions of migrant workers are forced to return to their rural homes. This implies that ASEAN now has a substantial rural population that suffers from the under-utilisation of digital technology.

Rural areas are disadvantaged due to the distance from major cities and low population density, which make the provision of quality digital infrastructure economically unviable without concerted public intervention. While the provision of broadband services should be a priority for attaining digital inclusion, only effective use of these digital technologies will enable rural communities to reap the full benefits. Closing the ‘access gap’ is important, but Moon et al. (2012) argues that ‘second-order effects’ of skilful digital usage must be sufficiently realised (as cited in Man et al., 2014). ASEAN and the ROK have cooperated extensively on promoting digital infrastructure development through MPAC 2025, but more can be done to promote effective utilisation of digital tools. Therefore, this paper suggests that digital engagement projects can be established in rural communities to promote the sustainable use of digital technology, modelled after the ROK’s Information Network Villages.

| Case Study: Information Network Villages (INVILs) in the ROK

In 2001, the ROK launched the INVIL to narrow the digital divide between urban and rural areas. INVIL caters to both demand and supply for digital technologies – it first provides residents with computers and digital infrastructure, then creates demand for digital use by encouraging rural residents to participate in the digital economy – selling local produce or promoting tour packages through the two central e-commerce websites established by the Ministry of Security and Public Administration (MOSPA). The revenues from the two INVIL online malls increased from USD$3 million to USD$40 million from 2006 to 2012. Each INVIL project is built around its particular community – a fellow resident is appointed INVIL manager and not only operates the training centre, but also addresses the residents’ specific needs (Man et al., 2014). |

In short, community engagement schemes are useful in imparting the skilful use of digital technologies to rural residents. This paper is optimistic that it will be well received by ASEAN members, given the encouraging precedent set by initiatives like Go Digital ASEAN. The ROK can partner ACCMSME and relevant bodies to pilot INVIL schemes in willing rural communities and could devote part of its ODA budget to support the implementation of these initiatives.

Digital Divide in Education

Digital literacy should not only be targeted at aspiring entrepreneurs or MSMEs. While the ROK has pledged US$6.9 million to the Technical and Vocational Education and Training Programme, more can be done to promote digital literacy from a young age (Lim, 2020). As Servon and Pinkett (2014) argue, the digital divide is not ‘binary…between ICT haves and have-nots. Rather, it should be understood as varied degrees of multiple layers of digital disadvantage.’ This makes digital literacy in early childhood education all the more essential to ensure that underprivileged communities gain an equal footing in the digital economy.

The paper proposes establishing a collaborative educational platform between ASEAN and the ROK, modelled after the European Commission’s ‘e-Twinning’ and ‘School Education Gateway’ initiatives. The EU digital platforms encourage ICT collaboration among teachers at European schools. Teachers who are registered users on the platform can form cross-border partnerships and work on collaborative pedagogical projects in various school subjects (European Commission, 2019).

Transposed to the ASEAN-Korea context, governments can look into setting up a web-based platform for educators or volunteers to co-create digital resources for students and training materials for teachers to transition to new forms of teaching, such as gamified learning or the use of classroom management portals. While countries within the region may have different curricula, they tend to teach similar subjects and could consider translating foreign digital resources that are aligned with their curriculum. The ground-up approach not only improves the quality and accessibility of educational resources, it also fosters meaningful people-to-people exchanges as teachers learn to design their teaching resources in a way that caters to a culturally diverse audience through these collaborations. In short, this solution not only rectifies the disparities in remote education but also promotes interpersonal cultural exchanges that will solidify constructive partnerships across borders for a worthy cause.

Overall, the section on digital inclusion proposes digital literacy solutions to improve prospects of employment and education in under-connected communities. In a hyper-digitalised world where mastery of digital technologies has become the pre-requisite for a better future, addressing digital inclusion will be a worthwhile investment for governments.

Connected Cities: Accelerating Smart City Development

Smart cities generally refer to initiatives that harness digital innovation to improve the delivery of urban services (OECD, 2019). This paper will specifically couch ‘smart’ as ‘climate smart’ – a term coined by the UN. Thus far, there is an ASEAN-Korea ministerial consultative body on smart city development and the ROK has also pledged support for the ASEAN Smart Cities Network. However, the ease of implementation of smart cities is ranked third in this paper due to high investment costs. Smart city development might take a backseat for now, given the focus on providing essential services during COVID. Nevertheless, the development of smart cities will bring long-term benefits by mitigating climate change and making urban areas safer and more inclusive.

Greenhouse of Smart Solutions: Tapping on the ASEAN-KOREA Start-up Ecosystem

At the 1st OECD Roundtable on Smart Cities held in July 2019, participants raised the need to involve start-ups and accelerators in smart city development (OECD, 2019). Indeed, they are valuable partners that can innovate ‘green solutions’ for cities, which remain an under-explored prospect for most countries in the region. Therefore, the paper suggests that the budding ASEAN-Korea start-up ecosystem can be harnessed to develop innovative climate solutions for sustainable urban development. This builds on the momentum set by ‘Startup Expo’, which featured in the ASEAN-Korea Start-up Summit in 2019 (The Investor, 2019). Such a regional start-up ecosystem could incorporate elements from Singapore’s Accredited Mentor Partners scheme.

| Case Study: Singapore’s Accredited Mentor Partners (AMPs) under Startup SG

Enterprise Singapore has appointed AMPs to support the dispensation of grants. The AMPs, which comprise industry leaders, incubators and accelerators, will evaluate the business plans of aspiring start-ups. Successful start-ups will be mentored by these AMPs under the Startup SG Founder and will receive advice, training and networking contacts in addition to the monetary grant (Startup SG, 2019). |

This presents a possible model for future incubation initiatives. In short, start-ups should be incorporated as key partners in smart city development, and smart solutions can be systematically cultivated through a regional incubation programme that maintains sustained engagement with start-ups by offering mentoring and training opportunities.

Digital Governance: Digitising Public Service Delivery

Last but not least, governments should cooperate to facilitate the implementation of digital public services. Gromov et al. (2018) highlight that residents who are ‘satisfied with a public service’ are nine times more likely to ‘trust the government’ than those who are not. Digital public services also reduce the administrative burden on public sector employees, by automating case handling for example. While ASEAN states have shown a willingness to modernise the public sector, digitising the delivery of public services is exceptionally challenging because of a shortage of requisite expertise, cultural and legacy roots that may be resistant to change, and the lack of strategic alignment on digital processes across the bureaucracy (McKinsey, 2019). This explains the decision to rank ‘digital governance’ last on the ‘Ease of Implementation’ scale.

While the ROK and ASEAN have pledged to ‘[promote] e-governance among civil servants’ in the Plan of Action (2021-25), there is little elaboration on how digital technologies can be incorporated into public sector reform (ASEAN, 2020). Therefore, there is value in holding regular conversations about the challenges of and strategies for carrying out a Whole-of-Government (WOG) digital strategy.

This paper proposes the establishment of an ASEAN-Korea ‘digital help desk’ under the Internet Governance Forum Plus. The Internet Governance Forum (IGF) is a global multi-stakeholder platform that discusses public policy issues relating to the Internet, and the UN High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation established IGF Plus in 2019 to contemplate future models of digital governance. This regional desk operates in alignment with the UN-wide Observatory and Help Desk. It will facilitate the sharing of best practices among countries, such as the customisation of front-end user experience of e-government portals and the standardisation of back-end systems (UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation, 2019). Such an initiative could leverage the expertise of other continents while maintaining a focus on the local context, achieving a balance of autonomy and perspective.

Conclusion

The future of ASEAN-Korea digital cooperation in the post-COVID era looms large in the minds of policymakers, business owners and ordinary citizens. This paper suggests that we should not fret, as there is much to anticipate. While the digital disparities within ASEAN and between ASEAN and the ROK highlight the possibility of incongruous goals, the onslaught of COVID has presented a compelling case for digitalisation and unveiled new areas of collaboration in which ASEAN-Korea interests can be complementary.

In sum, this paper proposes four areas of cooperation – accelerating the digital economy by leveraging the momentum of high-growth sectors, fostering digital inclusion by increasing digital literacy and encouraging the co-creation of educational resources, building smart cities by nurturing climate-resilient urban solutions, and digitising the delivery of public services through regular intergovernmental dialogue and mutual assistance. Digitalisation has now become a strategic priority for all governments alike – a fruitful partnership in this respect will allow ASEAN-Korea bilateral relations to grow from strength to strength.

References

ASEAN-Republic of Korea Plan of Action to Implement the Joint Vision Statement for Peace, Prosperity and Partnership (2021-2025). (2020). https://asean.org/storage/2012/05/ASEAN-ROK-POA-2021-2025-Final.pdf.

CARI. How COVID-19 will transform global supply chains and how ASEAN must respond – CIMB ASEAN Research Institute. CARI. https://www.cariasean.org/news/how-covid-19-will-transform-global-supply-chains-and-how-asean-must-respond/.

Chapco-Wade, C. (2019, May 21). In Korea, Culture Matters in the Social Media Landscape. Medium. https://medium.com/@colleenchapco/in-korea-culture-matters-in-the-social-media-landscape-e2fad0cd8043.

Cisco. (2019). Cisco Global Digital Readiness Index 2019. https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/investing-in-aseans-digital-landscape-new-opportunities-after-covid-19/ .

Enterprise Singapore. (2019, April 22). Startup SG – The Singapore Startup Ecosystem. https://www.startupsg.gov.sg/announcements/4910/enterprise-singapore-appoints-17-more-accredited-mentor-partners-to-startup-sg-founder-scheme.

Gromov , A., Pokotilo , V., & Sergienko , Y. (2018). What it takes to digitize a public sector organization effectively. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/the-organization-blog/what-it-takes-to-digitize-a-public-sector-organization-effectively.

Hoo, C.-P. (2019). The New Southern Policy: Catalyst for Deepening ASEAN-ROK Relations. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ASEANFocus%20-%20December%202019.pdf.

Jung, M. C., Park, S., & Lee, J. Y. (2014). Information Network Villages. Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, 2(1).

Kim, J. (2020, October 27). South Korea rebounds from COVID recession on export recovery. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/South-Korea-rebounds-from-COVID-recession-on-export-recovery.

Launched: ROK project to support ASEAN COVID-19 detection capacity – ASEAN: ONE VISION ONE IDENTITY ONE COMMUNITY. ASEAN. (2020, June 17). https://asean.org/launched-rok-project-support-asean-covid-19-detection-capacity/.

Lim, S. (2020, June 26). Strengthening Korea-ASEAN strategic partnership. The Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2020/06/26/strengthening-korea-asean-strategic-partnership.html.

Market Research Company Focuses On Providing Valuable Insights On Various Industries. VynZ Research. (2020, April). https://www.vynzresearch.com/healthcare/digital-health-market.

McKinsey & Company. (2020, September 28). What 800 executives envision for the postpandemic workforce. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/what-800-executives-envision-for-the-postpandemic-workforce.

Medina, A. F. (2020, September 16). Investing in ASEAN’s Digital Landscape: New Opportunities After COVID-19. ASEAN Business News. https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/investing-in-aseans-digital-landscape-new-opportunities-after-covid-19/.

Nortajuddin, A. (2020, July 15). The Rise Of Telehealth In A Pandemic. The ASEAN Post. https://theaseanpost.com/article/rise-telehealth-pandemic.

OECD, & Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport Korea. (2020). Smart Cities and Inclusive Growth. OECD.

Plecher, H., (2020, July 29). ASEAN countries – urbanization 2009-2019. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/804503/urbanization-in-the-asean-countries/.

Roy, I. (2020, June 25). Remote work: A Temporary ‘Bug’ Becomes a Permanent ‘Feature’. Deloitte United States. https://www2.deloitte.com/kh/en/pages/human-capital/articles/remote-work.html.

Servon, L. J., & Pinkett, R. D. (2014). Narrowing the digital divide: the potential and limits of the US community technology movement. The Network Society, 319–38. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781845421663.00027

Special Update on the 2019 ASEAN-Republic of Korea (ROK) Commemorative Summit. CARI. (2020). https://www.cariasean.org/special-update-on-the-2019-asean-republic-of-korea-rok-commemorative-summit/.

The Investor. (2019, November 27). [ASEAN-Korea Summit] Promising ASEAN startups showcase at ASEAN-ROK Summit. THE INVESTOR. http://www.theinvestor.co.kr/view.php?ud=20191126000842.

The Korea Herald. (2020, May 19). Seoul’s uphill battle in promoting telemedicine: Korea Herald. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/seouls-uphill-battle-in-promoting-telemedicine-korea-herald.

WEF. (2020, June 19). This Is How Blockchain Can Be Used In Supply Chains To Shape A Post-COVID-19 Economic Recovery. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/worldeconomicforum/2020/06/19/this-is-how-blockchain-can-be-used-in-supply-chains-to-shape-a-post-covid-19-economic-recovery/?sh=12fdedce4c0e.

Williamson, J. (2020, July 29). 60% of AI-powered manufacturers are using it to support workers. The Manufacturer. https://www.themanufacturer.com/articles/60-of-ai-powered-manufacturers-are-using-it-to-support-workers/.

Wongi, C. (2019). Why South Korea Wants to Tie In with ASEAN. ASEAN Focus. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ASEANFocus%20-%20December%202019.pdf.

World Economic Forum. (2018). Digital ASEAN. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/projects/digital-asean.

UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation. (2019). The Age of Interdependence. https://digitalcooperation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/DigitalCooperation-report-web-FINAL-1.pdf.

Yonhap News Agency. (2019, November 24). S. Korea’s trade with ASEAN nations up twentyfold since ’80s. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20191124000800320.

[1] The matrix compares the ease of performing an action and the benefits that it yields. The rational decision will be to prioritise tasks with the highest benefit and greatest ease.